“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

–Emily Dickinson

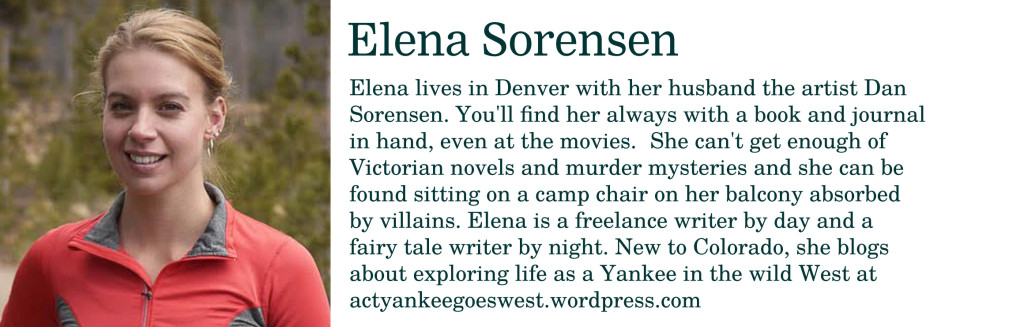

For the first part of the year I was hopeful for a job and to pay off debt. Now I’m hoping to leave my job, work for myself, and jump back into debt by buying a house. I’m also hoping to stay in a church I’ve found after years of searching, finding, backing away, and restarting the search.

Advent is a season of hope for me. It’s the tipping point into the New Year. It’s hope for the long-expected coming of the infant Christ. It’s the time of year I like the best. Contemplation, choral music, commercial cheer, even Walmart becomes a beautiful place to me for the first week or two of Advent.

Hope is the thing with feathers. It perches in my soul. I have always assumed that my life is the sum total of my experience in the world. That I’m a hopeless distance from attaining the wisdom and experience I should have. On my worst days, I believe life WILL probably end today, right now. But I look at Dan and see how quickly a year and a half together has gone by. That there has been such healing for me inside my marriage, and I hope and trust that we have many more years together ahead of us. Hope is like a cold I keep catching and giving to myself.

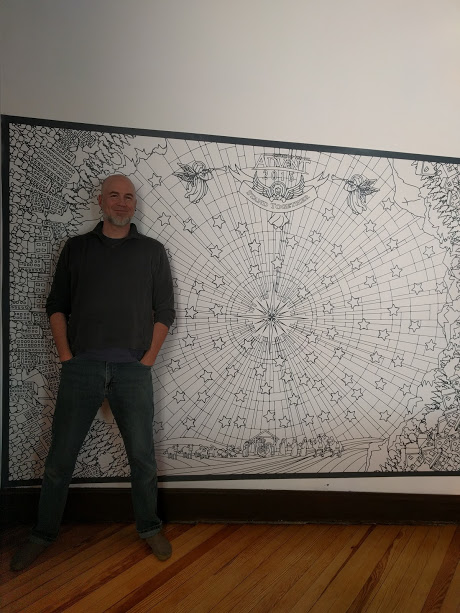

On Saturday, Dan took to our church a huge paper mural he created for the members to color on through Advent. We don’t know many people there yet and I hope we will stick it out before wanderlust and the old feelings of being at odds with church set in. It’s hard to enter a new compact with people we don’t know well. To show up week after week with others and say, “Hello, I’m here for you even though I don’t know you very well and we keep forgetting each other’s name.” To look longingly at others’ children and wonder if it’ll happen for us. But we keep showing up, hoping for Advent and for friendship. The paper mural is part of that. Hope, as Emily Dickinson says, is the tune without words that never stops. It’s the song stuck in your head you wish would go away, even as you hum and tap your fingers to it.

The mural is a thing of beauty. It is the best of Dan’s art. It’s whimsical and playful, big and generous, and the priest loves it. Everyone immediately began to draw and write prayers on it. It’s public but intimate—just like Advent. The mural was pristine when we put it up Saturday and on Sunday it became imperfect. It was covered with the eager fingers of children who colored in the Star of Bethlehem with black Sharpies, ignoring their parents’ requests to color in the lines and to please use the eighty beautiful hues of markers and pencils available. Like the little bird in the poem, these children are unabashed. They hope they can finish the coloring job unimpeded, by the end of Advent.

This morning at church I spoke with a woman I met last week. It was a glad meeting of recognition. We’re trying to become friends. I even remembered her name, Sarah. Our greeting was formal, warm and over too soon. I walked away out of countenance. But it’s the hope of friendship that makes me press forward. We’ll talk again. We might even let slip one or two revealing opinions about the election or other people we know, and we’ll wonder if it’s alright to say them out loud in church. And we’ll look at each other sheepishly and our friendship will really begin. Hope doesn’t need anything from me, not even a crumb. Just belief. It will precede every friendship and every encounter in this church, in this city, in this life.