“Shhhhhhhhhh!”

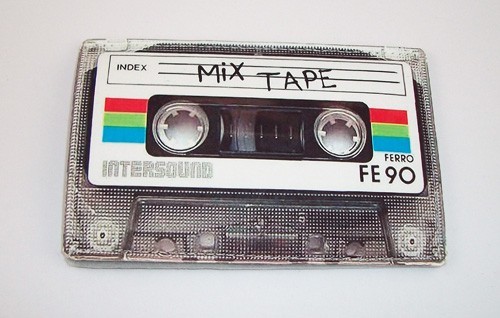

My exasperated, whispered command to be quiet is the loudest sound on the cassette tape. Repeatedly.

Through the whir of the nearly 40-year-old tape, I can hear the giggles of my younger brothers fade beneath the laugh track. Marie Osmond is singing about how she’s a little bit country, and her brother Donny is responding that he’s a little bit rock’n’roll. I hear the shuffling click that signifies a commercial break, abruptly followed by the resumption of the intro music and laugh track.

***

It’s just before 8:00 on a Friday evening in the fall of 1977, and 11-year-old me is crouched on the shag carpeting in the family room of the house on Mt. Vernon Drive. While my mom, dad, and brothers lounge comfortably on the sectional couch behind me, I zealously guard the channel and volume dials of the console color television like it’s my job. My fingers are poised over the play and record buttons of the cassette recorder. As the clock strikes eight, I press down.

It’s just before 8:00 on a Friday evening in the fall of 1977, and 11-year-old me is crouched on the shag carpeting in the family room of the house on Mt. Vernon Drive. While my mom, dad, and brothers lounge comfortably on the sectional couch behind me, I zealously guard the channel and volume dials of the console color television like it’s my job. My fingers are poised over the play and record buttons of the cassette recorder. As the clock strikes eight, I press down.

I am living in a time long ago and far away, before the proliferation of remote control devices or video cassette recorders or cable television. The likelihood of a member of my family storming the TV to change the channel from ABC to one of the three other options is unlikely. But I am not taking any chances.

There are six days and 23 hours between now and when the next Donny and Marie Show episode will air. By that time, I will have memorized the script and the songs of this one—and every shushing sound I make. From the opening musical number and ice-skating routine through the corny skits to the farewell strains of “May tomorrow be a perfect day,” I will have replayed in my head the images on the screen over and over. And over.

***

It’s August 1984, and nearly 18-year-old me is crouched on the shag carpeting next to the stereo system in my bedroom. This state-of-the-art piece of technology allows me to play a vinyl record or an eight-track or cassette tape. It also gives me the option to record from LP to cassette without the interference of outside noise.

I unwrap a blank cassette and click it into the front-loading slot. I press the play and record buttons just before dropping the needle into the groove of Supertramp’s Breakfast in America LP. I hum along with “The Logical Song” and “Goodbye Stranger” as I clutch my blue ballpoint pen and painstakingly copy the playlist from the record jacket to the lined cassette cover.

I unwrap a blank cassette and click it into the front-loading slot. I press the play and record buttons just before dropping the needle into the groove of Supertramp’s Breakfast in America LP. I hum along with “The Logical Song” and “Goodbye Stranger” as I clutch my blue ballpoint pen and painstakingly copy the playlist from the record jacket to the lined cassette cover.

A growing stack of freshly recorded tapes is piling up on the floor next to the radio/cassette “boom box” I will be taking with me for my freshman year of college. My dorm room will not be large enough to hold my growing record collection, let alone a turntable.

There is a token Donny and Marie Show tape at the bottom of the stack, beneath Prince’s Purple Rain, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A., and Tina Turner’s Private Dancer. I will listen to that one when my roommate is not around.

***

It’s late June afternoon in 2006, and I have set up my laptop computer on my parents’ kitchen table, where I can enjoy the breeze wafting through the screen door. Mom is napping in her bedroom, recovering from her latest chemo treatment. Dad is on the golf course, taking a break from his nursing duties, and my brother and niece will be joining us for dinner in a little while. I am taking a break from laundry and food prep.

My iTunes library is displayed on the laptop screen, and I make a selection from the stack of compact discs from my parents’ collection—greatest hits compilations from Johnny Cash, Neil Diamond, Anne Murray, Kris Kristofferson, Helen Reddy, and Tom Jones. These are the CDs my brothers and I have given to my mom and dad for Christmas over the years, meant to replace worn vinyl LPs with their scratches and skips. This music—in addition to Supertramp, Culture Club, Billy Joel, and my extensive Osmond discography—is the soundtrack of my childhood.

I click a Carpenters disc into the CD drive of my computer and select “yes” to begin importing the tracks.

I walk over to the refrigerator, pulling out the makings for a salad. I chop cucumbers and tomatoes to the accompaniment of Karen Carpenter’s soothing voice. I shred lettuce to the melancholy strains of “Yesterday Once More.”

***