When I was a little girl with two brown pigtails and bangs cut straight across my forehead, home was a grey-blue ranch-style house situated in the middle of Michigan’s palm. It was also a musty-smelling blue canvas tent, the sweaty brown vinyl backseat of a station wagon, and the open road, always leading to someplace new.

* * * * *

If “home” is defined as a specific place, then my answer to “Where are you from?” is clear: I’m from St. Johns, Michigan, a town of about 12,000 people with a two-stoplight Main Street that’s anchored on the south end by a classic Midwestern courthouse. My parents still live in the house they bought when I was just five, and when we visit today, my own daughters sleep in my childhood bedroom.

All the kids who went to my elementary school lived in town like me, but by the time we were in middle school, our classmates were pretty evenly split between “town kids” and the “country kids” who grew up on surrounding farms. (My best friend Rhonda was a country kid with horses we rode on the weekends.)

Besides sleepovers and football games, there weren’t many parent-approved things to do for fun, at least not until we were old enough to drive the half hour to Lansing for date-worthy restaurants, movies, and malls. But St. Johns was a good place to be a kid. Growing up in a sheltered town meant plenty of freedom to bike everywhere—the city pool, friends’ houses, the library, and the bakery for custard-filled long johns. We didn’t wear helmets or lock our bikes—the only requirement was a wristwatch so we wouldn’t be late for dinner.

But even with such deep roots in a single place, I also grew up with an understanding of home that was nomadic: Home was wherever you stopped and pitched the tent when it was time to cook dinner.

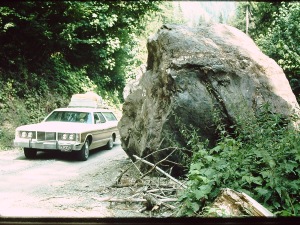

My parents were both teachers, which meant summers offered more time than money. Flying from Michigan to visit relatives on the West Coast wasn’t in the budget, so each summer we packed up our wood-paneled station wagon and hit the road for about six weeks.

I was prone to carsickness, so there were just two ways I rode in the car: sprawled asleep across the backseat or awake and perched dead center, leaning forward until I was almost as much in the front seat with my parents as I was in the back. Luckily, my big brother was never the sort to draw a line down the middle of the seat and enforce it with punches or pinches. Besides, I think he was happy to let me chatter away to my parents, leaving him in relative peace with his books.

The ultimate destinations we drove toward—a visit with our grandparents in L.A. or our favorite cousins in Portland, a week spent hiking in Glacier National Park, or a few days exploring San Francisco—were well-worth the 5,000-or-so miles we covered each summer. But so many days were devoted to just getting there, driving through endless-seeming states like Nebraska or North Dakota, only stopping for gas, bathroom breaks, and to eat the sandwiches Mom had made at the campground that morning.

After a full day of driving, as the sun was lowering in the sky and Mom’s voice was hoarse from reading aloud Little House on the Prairie books, we pulled out a thick campground guide and chose a place to stay—with a pool, if my brother and I were lucky. At the campground, Mom pulled out the camp stove and started dinner while the rest of us got to work setting up the tent and filling it with sleeping bags and pillows. The next morning it all came down again, was packed back into the car, and we drove some more—to the next place we would call “home” for a night.

* * * * *

Now, when I think about where I come from, I still envision that ever-present grey-blue house, first. I am very much a small-town Michigan girl. But it occurs to me that my rootedness in that place has always been filtered through an understanding of other places—of treeless plains and impressive peaks, of rugged beaches with magical tide pools, and of Chinatowns and subways, operas and contemporary art. I knew where I was back home in Michigan because I also knew where I wasn’t.

And in that sense, I come from places that protected me as well as places that exposed me—from a small Michigan town and big Montana mountains; from the inside of a station wagon, where my entire family was always close enough to touch, to a crowded San Francisco sidewalk where strangers pressed in as I absorbed glimpses of the world.

Photographs by William E. Tennant

Photographs by William E. Tennant