A damp chill in the early morning air, unusual for April this far south, makes me shiver. My azaleas and dogwoods are laden with buds yearning to give a color show of pinks and whites.

“Maybe my wisteria will be in bloom when we get back,” I say to myself.

“Come here and tell me what you think,” Tom calls.

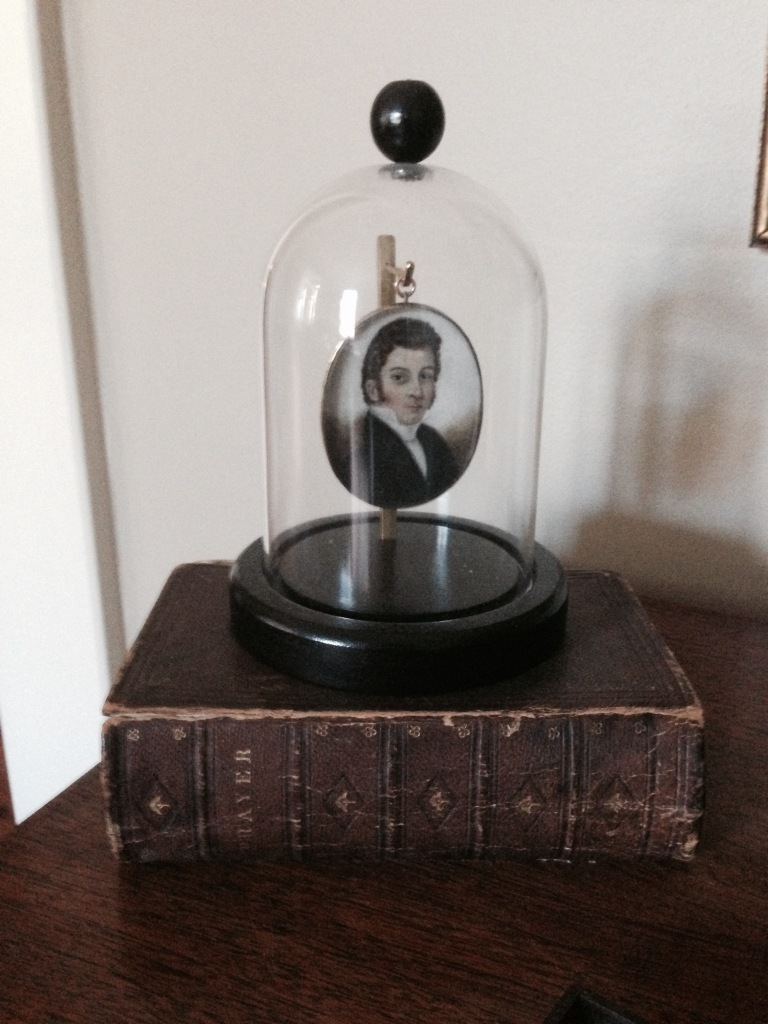

Milk crates and boxes filled with antique glass bottles are packed in the rear cargo hold of our SUV. Like a chess player contemplating his next move, Tom, my husband, is surveying the situation—rotating the multi-sized containers until he makes a space for “just one more.” We are preparing to leave for a collectibles show and sale in a small Virginia town nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

“Where in the world are we going to put our luggage, our clothes on hangers, and my tote bag? I ask.”Something’s got to give.”

***

The April tax crunch and an impending audit of our family business have pressure-cooked the creative juices and energy out of me. Tom rarely smiles. Our tempers flare—often. Silence follows. We’ve settled into a rhythm: Work. Sleep. Eat. Work. Sleep. Eat.

Five hundred miles of interstate stretch from Memphis to the Virginia state line. West to east we follow a route we have traveled many times. Tom drives, with a slight hunch of his shoulders, leaving a space between the seat and his back. I absentmindedly reach over and rub his back, circling my fingers over flannel and the nape of his neck.

I see cows graze in a pasture, dots of black scattered across a pasture of brown and patchy green.

“There are your cows,” says Tom with a knowing smile.

As I begin to tell a childhood story about my pet cow, I stop myself and apologize for re-hashing a tale he has heard many times during our 30 years together.

“It’s okay,” he says. Tom smiles, reaches over, and squeezes my hand.

Nearing Nashville, the road begins a gentle climb, bordered by an irregular wall of layered rock. Small trees struggle to maintain their footing as they grow through crevices in the stone. A few reddish brown leaves have hung on to their spindly branches since autumn.

***

A sign greets us: Welcome to Virginia. Virginia is for Lovers. The interstate winds slowly, flanked by deep ditches and streams of water littered with broken Styrofoam, food wrappers, and beer cans. Tidy white clapboard houses, with painted shutters and porches for sitting, live in the shadow of houses with unhinged shutters and collapsing porches.

JESUS IS LORD. WE SELL GUNS. proclaim the signs nailed side by side on the back of a weathered shed with a rusty red metal roof.

“Oh my goodness!” I exclaim. “I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

Our route leads us off the interstate to a two-lane highway with the occasional pothole. I hear the tinkle of shifting glass in the back of the vehicle and gasp. Tom assures me his careful packing will protect the fragile bottles from breakage.

Spring is coming slow here, also. The forsythia is starting to splash her cheerful yellow against the canvas of winter’s lingering gray. Slips of green are pushing through the pea-gravel at the side of the road. The mountains rise above this plateau, inviting us to travel to higher ground.

photo by Lisa Phillips