In the quiet, we huddle together and scold those who speak too often or above a whisper. I shift my weight carefully on the old wooden floors of the closet that protest with creaks at even the slightest movement.

Eight of us have piled into the utility closet off of the church parlor and are waiting for the rest of the “sardines.” Every muscle in my body tightens with the anticipation of voices or movement from the other side of the door. The must of old choir robes mixed with the generic old church smell that gets trapped in between the pages of pew Bibles and hymnals is particularly dense in our close quarters.

dense in our close quarters.

A paper palm frond tickles my elbow, the trunk of its tree standing tall in a bucket of cement. This prop is one of many artifacts left from Vacation Bible Schools and church events where the sanctuary was transformed into a tropical Island or the Sydney Olympic games, depending on what the Sunday School curriculum companies were pushing that year.

There are only so many spots in the church building that can fit all the sardines attending youth group on any given Wednesday night. Each hider imagines they will find the new, most secret of spots. Everyone ends up in the same rotation of hideouts: the closet with the Christmas pageant outfits and fake floral arrangements, somewhere under the pews in the choir loft, or this closet off the parlor where we wait now for the rest of the kids to find us.

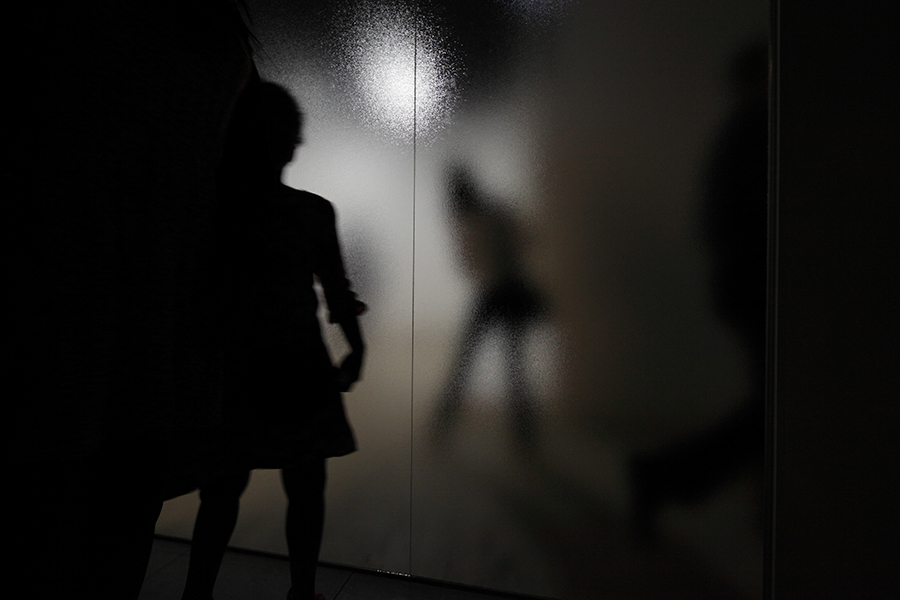

Once I join the cloistered youth group members, the act of hiding alerts my dormant primal instincts to survive. We all become prehistoric cave people, sheltering ourselves from a wooly mammoth, and we communicate with grunts and nudges in the darkness of our enclosure. We are alert, ready for fight or flight, knowing that at any second we many be startled by someone looking for the group hiding spot.

There is no real threat among the signs for long passed rummage sales and supplies used for church coffee houses, but for the thirty minutes the game lasts, we are in mortal danger. In the dark, in the secret place, we belong to each other. We are at the mercy of the loudest sneeze or the kid who clumsily knocks something glass off of the shelf.

Next to me, a girl leans into her boyfriend, emboldened by the covering darkness and closeness implied in the game of Sardines. One person finds a hiding place, and everyone who finds them must join the person in that spot. You win if nobody finds you, you lose if you’re the last one to find the group. In a couple of years, someone would wise up to the fact that shoving a bunch of horny teenagers into a small dark space wasn’t the best move for promoting a culture of chastity and purity.

It’s very popular to bring your boyfriend to youth group. I had a grand total of one boyfriend during my middle school and high school years, and we were too shy to interlace fingers during the gathering time or to cuddle during movies at lock-ins. In the presence of my peers, my limbs and extremities became clumsy and sweaty, each finger unable to coordinate with its neighbor to reach out and show affection.

The boyfriends who came to youth group were often sullen, tall boys with baggy cargo pants and shirts silk-screened with bands whose faces were frozen in eternal screams. Some wore sweatshirts made from the material of Mexican blankets, while others had long hair that hung down over their eyes.

We were encouraged to bring our friends and boyfriends, an evangelism tactic as old as the tent meeting revivals held by our ancestors, or perhaps as old the four men who lowered their paralyzed friend to be healed by Jesus. All the same, friends and boyfriends were brought to church to hear the gospel or to play ultimate frisbee or to eat a shake made from a blended happy meal.

I often found excuses to slip away during the loud games that ended with youth group members accidentally putting their hands through windows or face planting on the cement floor. In these situations, I imagined that all eyes were on me, ready to notice the way my feet bowed out when I ran or the inevitable sweat circles under my armpits.

Sardines was the great equalizer.

We are in the dark, we are all the same, we must not make a sound. I am caught up in the energy of the game. In an era when I am most singled out and exposed, I am blissfully anonymous, another set of shadowed shoulders, a counted head as we wait for the next youth group member to join. All I needed to do was find my people, to wait and breathe, and be.