I curate a small store of relics from my years teaching in Chicago—

c rayon-drawn cards, apology notes with misspelled superlatives, and portraits where the size of my head dwarfs my torso. In one early drawing, a student depicted me with flowing red hair and a bikini. I have two guns in holsters at my hips and a rainbow behind me.

rayon-drawn cards, apology notes with misspelled superlatives, and portraits where the size of my head dwarfs my torso. In one early drawing, a student depicted me with flowing red hair and a bikini. I have two guns in holsters at my hips and a rainbow behind me.

I’ve packed away most of my memorabilia in a catchall file in our spare bedroom, trying to organize and place memories from a time that spilled outside of any boundaries I tried to create for it. One lone tongue depressor has made it through three apartment relocations and three school changes. Each time, I considered tossing the stick, but I always ended up keeping it, laying it back amongst my pens. It’s small enough, important enough to keep.

It’s Corvell’s stick. I met Corvell in my first year of teaching, and he was my first student to disappear.

I showed up to teach in Chicago’s inner city with more experience teaching stuffed animals than actual children. I took the alternative certification track to gain my teaching credentials along with many non-teacher types who cared about social justice and/or had seen the documentary “Waiting for Superman.”

We came tugging our  liberal arts educations behind us, hailing from some of the top universities in the country and swearing our scout’s honor that we worked hard and could make it through a few years teaching in the inner city.

liberal arts educations behind us, hailing from some of the top universities in the country and swearing our scout’s honor that we worked hard and could make it through a few years teaching in the inner city.

By my second week student teaching, my childhood expectations of education came undone. When I played school as a kid, I propped my stuffed animals into position, neatly stacking papers and fastening them with paper clips. I taught my plush class whatever I wanted, and ears full of cotton, they still listened. Back then, I mimicked the lessons delivered by my own teachers, tidy women with pant suits and coordinating jewelry.

My teaching experience looked nothing like this, I looked nothing like this. My days didn’t form into an inspirational narrative, but instead finished with a sense of mere survival. Instead of matching jewelry, I wore hardened streaks of oatmeal on my coat from eating on the way to school.

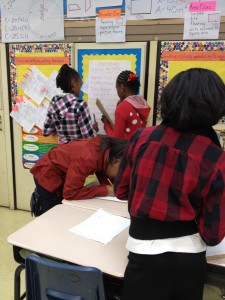

Teaching overflowed into every corner of my life. Jayla’s empty stomach leaked into my thoughts at night and lesson plans edged into spare weekend hours. Carefully constructed reading activities got interrupted and sloshed aside to be buried under math tests and leveled readers. The education system proved much sloppier than I ever imagined. And yet, Corvell’s disappearance still knocked the wind out of me.

His Dad picked him up for an early dismissal, and by 3:00 p.m., we got his transfer papers. Someone at the school called DCFS on Corvell’s parents. This report added to many others on file, and as had become their custom, the family moved onto a new school, away from the prying eyes of the well-meaning teacher who called in the report of neglect.

The principal and case manager did not bat an eye. They told me the news as a point of business. The school secretary laughed at my shock and said, “One less copy to make!” Corvell’s story was a familiar one in Chicago, but I was still a newbie.

That day after school, I cleaned out his desk, slid his reading circle book back into the classroom library, and cancelled other evidences of him around the classroom. I pulled Corvell’s stick from the small tin bucket with a whole class set of tongue depressors inscribed with each student’s name. My co-teacher and I rifled through the sticks when eyes got sleepy during a read aloud or when only a few hands darted up in a math lesson. If I drew your stick, you were on the line, responsible as the next person for our classroom learning.

The last time I worked with Corvell, I made him cry. I told him he wasn’t trying hard enough on his reading test. As I chided him and repeated the test question again, his usually swinging legs held still. He traced over his name with his pencil again and again as he let tears splash on his paper. And that was the end of our story.

There was no shiny ending, no epiphany. I stowed the stick in my desk, to remember Corvell always, to remember the lesson learned that day, that kids sometimes disappear.

I grew accustomed to Corvell’s story or one’s like it.

I stopped keeping mementos for each student. Corvell’s stick has become the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, the memento to represent my utter lack of control over the faces in all of my classrooms. For a year, or sometimes less, I poured my whole self into my students, thought about them, fixed their hair, wiped their tears, went to bat for them, drew smiley faces with ketchup on their burgers, and then they disappeared into chaos.

My last year teaching, I lost track of Corvell’s stick and found it while drawing sticks out of the jar of tongue depressors in my first grade classroom. My co-teacher must have found it and decided to repurpose it for another student in our room. Like any relic, its meaning was held in the knowledge of the one who owned it, like the rag of an apostle’s robe or the heel bone of a saint.

for another student in our room. Like any relic, its meaning was held in the knowledge of the one who owned it, like the rag of an apostle’s robe or the heel bone of a saint.

I looked at the faces of my first graders and thought of the ones already missing from their rug spots. Now my fourth year in the classroom, I’d better learned how to rise above the rubble and teach in the moment, but I still mourned my Corvells.

He was every student I couldn’t help enough, couldn’t reach, couldn’t follow, or hold forever. He was every student from my years in CPS, kids I cared for deeply and will likely never see again.

***