I watched from a few feet away, holding her bouquet of gray lavender roses, as she gazed into his eyes and said those sacred words of promise, “I do.”

It was the destination wedding that we had daydreamed about years earlier, laughing and letting thoughts run wild. I had trouble going too far into my hopes for the future, but she was clear: a refined wedding, intimate with only a small group of friends and family. Now, in the glorious splendor of the Colorado mountains, her dream had just come true.

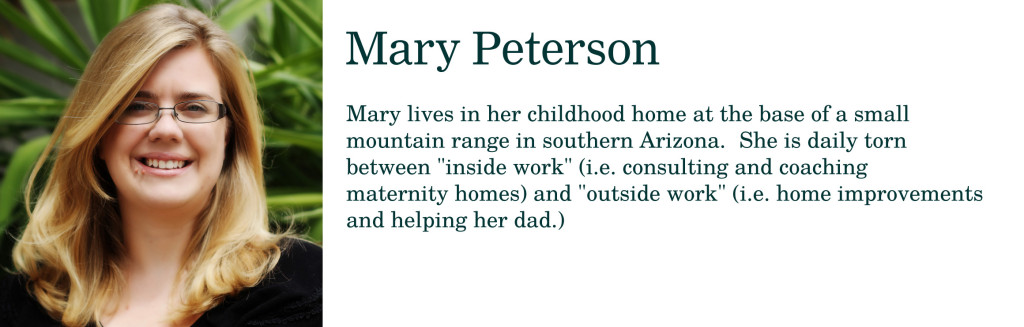

In our first days of college, she turned to me and extended her hand, “Hi, I’m Sheri.” Her eyes sparkled with confidence and energy.

Mass was over and people were in small groups chatting. I had been trying to shyly sneak out the side door when she caught my eye. “Hey,” I replied, fumbling a bit, ”I’m Mary.”

“Oh!!!” she replied with a small squeal, “Sheri! Mary! They rhyme! We should do dinner!”

“Hmmmm, yah, okay.”

And so it began.

In the dark basement of the student union, she chatted freely. Basketball. Classes. The dorm. And, she did her best to draw me out. Home. My major. The university. I was a bit taken aback by the dynamism of her personality and sat deep in my chair, a bit shell-shocked. But that dinner connected us, the first link.

Soon, we were meeting up to walk to Mass together and dinner afterward became a norm. Eventually, we started to talk about very real things, storing each other’s thoughts and pains in the vault of friendship.

Among the things that I learned at college, Sheri taught me how to be a friend.

As the years passed and our friendship remained, I gained the confidence to refer to her as my “best friend.” I was honored and humbled when she asked me to be her maid of honor, but in reality, it wasn’t much of a surprise.

As she prepared for her wedding, I enjoyed getting regular updates, hearing about the details as they unfolded. There were a few mini-dramas planning a wedding a few states away, and I listened attentively as the bumps got smoothed out. The right paperwork got into the hands of the deacon, the cake baker started returning phone calls, and the awkward conversations about the abbreviated invitation list were carefully handled.

Somewhere in the process, a thought began to irritate me, a tiny sliver under my skin that kept pricking me during the joyous preparations, even though I tried to ignore it: What would marriage mean for our friendship? It was right and good that he was now the one to plan things with, the one to hold her hurts and dreams. Would I still have a place?

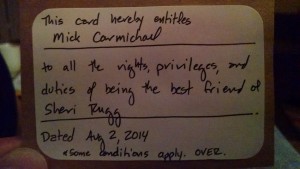

I made light of this tiny fear, raising my glass to toast the newlyweds at their reception. In front of all the guests, I presented her husband with official recognition that he was now entitled the title “best friend.” I would retain the rights to the girly stuff.

I gave that toast a little over a year ago, an eventful year of  ups and downs. A year of phone calls sharing good news and tears. A year of advice as decisions were made and support as hard times were confronted. A year of visits and gifts and travel.

ups and downs. A year of phone calls sharing good news and tears. A year of advice as decisions were made and support as hard times were confronted. A year of visits and gifts and travel.

The stuff of gold, our friendship remains: a relationship with history and weight, with vulnerability and trust. The sliver of doubt which nagged me during wedding preparations is gone, the tiny wound has healed. My place is secure. In becoming one, Mick has been joined into our bond of friendship. He is a wonderful man–gentle, insightful, authentic. He loves Sheri and I love him for it.

Last week, I sat on the couch of their living room and held their first-born daughter, less than three days old. She was perfect, a truly beautiful baby. Her limbs were still curled up as if she were contained, the occasional stretch exploring new-found room. They recounted her birth story, filled with the intimate details that you only share with a tight knit group.

They are calling her “Lizzie”, in short for Elizabeth Marie.

They are calling her “Lizzie”, in short for Elizabeth Marie.

I asked about the process for choosing her name. In the confiding voice of a long-time friend, Sheri leaned her head just so and said, “Mick loved the name….and when he learned it was your middle name, he said, ‘Even better!’”

With silent joy, warmth filled my heart. Tracing my finger down Lizzie’s cheek, there was no doubt.

Love multiplies.

***