Fifteen years ago, I remember my mother-in-law, a lady from the Eastern Shore of Virginia, saying to my husband Tom and me: “I want to start giving you the family things so you can enjoy them, and the children can grow up with them.”

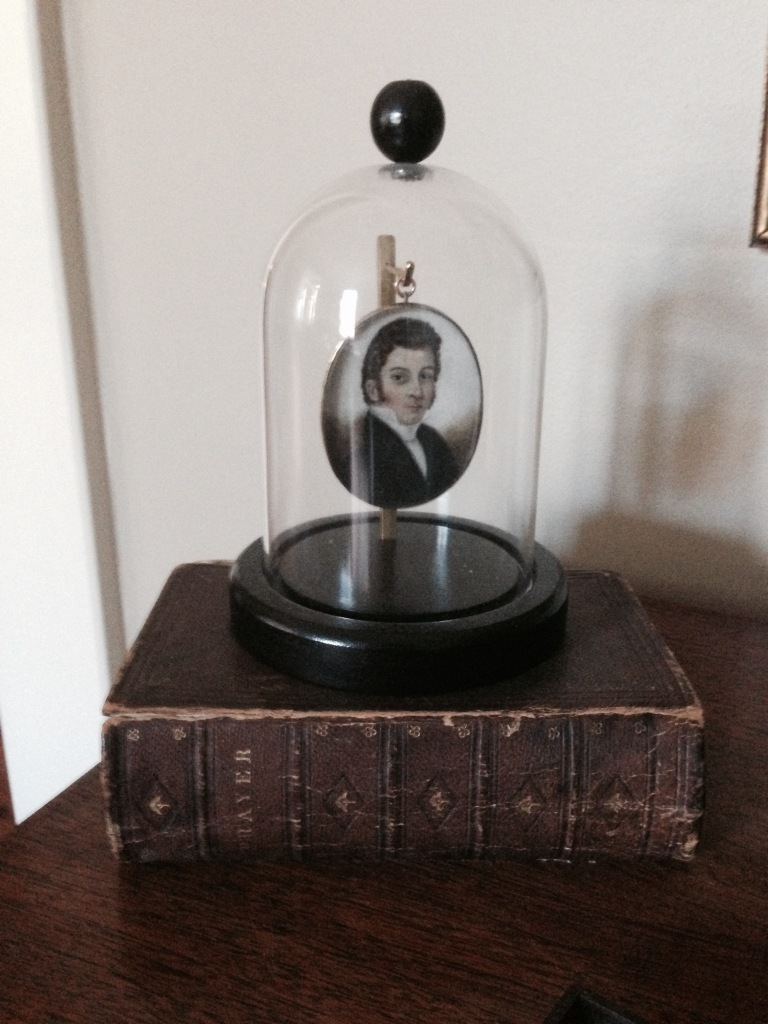

Since the time she entrusted us with the family heirlooms, I have endeavored to give them meticulous care without creating a museum-like atmosphere in our home. Our children have learned to appreciate their heritage because of the stories told by their grandmother, ones in which they are related to the settlers of Jamestown, U.S. Presidents, scalawags, crazy aunts, and sturdy women who saved the family furniture during hard times. The silver, china, books, and furniture handed down to us are not “just things,” but they reflect the lives of those whose faces speak from their portraits on our walls.

*****

My favorite part of preparing for Thanksgiving is when I hide in the silver closet like a Confederate hiding from the Yankees. I pull out silver place-settings, serving pieces, bowls, trays, goblets, and napkin rings. The late nineteenth century Haviland Limoges china, delicate, but durable, is arranged in my china cabinet. I hold my breath and move in slow motion as I retrieve dinner plates, bread plates, butter pats, serving bowls, and meat platters from the shelves.

Everything is carried to the dining room, and I begin to dress the table based on the number of guests I will feed, and the dishes I will serve. I think to myself: Will I use napkin rings or tuck the napkins under the plates? Tablecloth or place-mats? Iced teaspoons?

I fuss over the details of creating an inviting table, not one that is high-brow, (dinner attire is flannel and denim), but a table-scape of respect and gratitude for the women of past generations who set this family table for Thanksgiving.

A cooking marathon begins in my kitchen on Thanksgiving morning and by dusk, the turkey is resting plump and tender on the Haviland platter. It is time to dim the lamps, light the candles, and call our dear ones to the table. Tom usually interrupts the loud, pre-dinner banter, but sometimes our son will play the antique tabletop chimes to announce that dinner is served. A blessing of praise and gratitude is prayed. When the eating begins, the room grows quiet except for the “mmms” heard as we taste the richness of the food. Hearty appetites satisfied give way to hearty laughter, and everyone pushes back from the table and begs off dessert until later.

A cooking marathon begins in my kitchen on Thanksgiving morning and by dusk, the turkey is resting plump and tender on the Haviland platter. It is time to dim the lamps, light the candles, and call our dear ones to the table. Tom usually interrupts the loud, pre-dinner banter, but sometimes our son will play the antique tabletop chimes to announce that dinner is served. A blessing of praise and gratitude is prayed. When the eating begins, the room grows quiet except for the “mmms” heard as we taste the richness of the food. Hearty appetites satisfied give way to hearty laughter, and everyone pushes back from the table and begs off dessert until later.

I am weary, but satisfied, content to linger at the table. I think about the father-in-law I never knew who, forty years ago, sat at the head of this table and buttered his bread and stirred his iced tea with the silverware that bears his monogram. My husband and children have the same monogram engraved into their DNA, and with His gracious pen, God has written me into the same story.