And I would do it again, but set down

This, set down

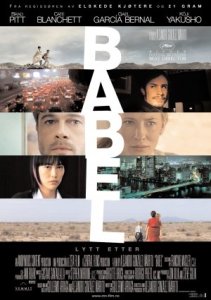

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death?

– T.S. Eliot, The Journey of the Magi

Let your beauty manifest itself

Without talking and calculation

You are silent. It says for you: I am.

And comes in meaning thousandfold,

Comes at long last over everyone.

– Rilke, “Initial”

At the risk of proving too dim – more so than usual – how in the world do you even begin a tradition? And how do you decide which traditions to adopt or dismiss? What makes our family traditions lasting, what makes them stick?

At the risk of proving too dim – more so than usual – how in the world do you even begin a tradition? And how do you decide which traditions to adopt or dismiss? What makes our family traditions lasting, what makes them stick?

These were and are my burning questions this holiday season, beginning – as I described in my last post – this recent Thanksgiving, accompanying me through Christmas yesterday, and traveling with me into the coming New Year. This year I admittedly found myself at a loss. Part of the reason for this conundrum was because, having just flown East for my brother’s wedding in Philadelphia this summer, there was no way to afford another trip from Alaska to the East coast this holiday season. However, I think, too, this mostly-financial matter only forced me to face a deeper, ultimately unavoidable fact of my situation as a single father up here in Alaska, far from Pennsylvania, my home place of origin:

What am I offering these boys, who, at ten and six, are rapidly passing through boyhood and coming of age in a landscape and time period so vividly and markedly different from my own? And how do I attempt or manage to shape anything resembling traditions, for now at least, mostly solo and on too-frequently-limited resources? And how can I deliver legitimate holidays to my boys that don’t blithely or solely coast along the thin surface of the media, Target, or Amazon.com versions of what the day supposedly means?

Over the nearly four years since my sons’ mother and I split up, I found familiar comfort and reliable ease in flying the three of us east to spend the holidays with my family. This effort required little to no thought in my mind, no question of the role I assume or play in the context of extended family, or what I’d be offering Sam and Matt once our plane touched down. Order the gifts early enough online that they’d be at my parent’s house before our arrival and then Sam, Matt, and I would just effortlessly slip into the stream, the flow of everything I’ve inherited throughout the all-American, uber-traditional holidays of my own childhood.

Admittedly, the traditional Bower family Christmas back east has for as long as I can remember also been defined by nothing less than a requisite degree of full blown, manic chaos. Albeit an adorable, welcome brand of chaos, largely because the holidays are perhaps the lone, annual opportunity to find every niece, nephew, sibling, cousin, aunt, uncle, and surviving grandparent reliably collected in one place, even if it is at the price of temporary insanity for all involved.

Though an entirely well intended, big-hearted affair replete with randomly occurring acts of familial affection – walloping to near-smothering hugs, earthquaking belly laughs, spontaneous guitar jams and more – the day is no less defined by a never long-sustainable level of noise and borderline confusion. These are riotous events that reliably tax every child’s emotions, ultimately requiring that some assortment of offspring collapse in tears before we can really determine whether the day proved successfully over-stimulating enough or not. Our gatherings have also been annually governed by the persistent din of new devices being fired up or tested, new instruments relentlessly strummed or pounded on, new stereos and/or albums blaring from multiple corners of the room. Of course, someone also always receives the one toy that will send the terrier into a yapping frenzy. It’s a brand of nuttiness that leaves the adults gleefully resigned to caffeinated autopilot from shortly after morning coffee until they can collapse for the rumored winter’s nap at night’s end. By evening, the day’s relentless barrage of good cheer and sugared, fatty foodstuffs and shiny new material possessions and the full brunt of unending social engagement finally reaches critical mass, driving a select batch of us – those too cowardly or soft to live the teetotaler lifestyle of our forebears – to covertly duck into a secret room or to launch out back to grab a nip of an adult beverage. That small band of us pauses and breathes outside, some anxiously grasping for their smokes as we attempt to sit still long enough to raise a glass in the nearest dark space we can find that will afford us a moment’s respite or silence…

Every year in Alaska’s deepest, darkest winter hours, I’ve longed for this single day of unsustainable chaos the way I imagine the polar explorers longed for the affections of their faraway wives and the comforts of home.

The question of traditions and rituals we instill among family – blood relations or adopted or “friend” families – seem to me actually part of the larger question of how you in fact make a home…which is precisely what I’ve circled the wagons trying to do since becoming a single parent a few years ago.

And so, with no ready-made or fixed traditions in place, this holiday season became a kind of riddle, a query lobbed to no one but myself, especially since both my sons, born and raised (so far, mostly) here in Alaska identify no other place they’ve visited or traveled to as home:

What if (huge gulp) we were already home for the holidays?

And, on that notion, what if we started making a day that grew (sanely, maybe even quietly) out of – in the words of Andy Williams, from a Christmas album that has since childhood marked the arrival of the holiday in my mind – “a few of [our] favorite things”? What if we dared test the waters of a new, different stream, perhaps even one that proved a little less chaotic? What then?

We attended the 11pm Christmas Eve service at the Episcopal church we frequent, because Sam was scheduled as an acolyte that evening. Afterwards, close to 12:30am, he raced up to me, bleary eyed and still in his robes, and threw his arms around me announcing, “Merry Christmas!”

We attended the 11pm Christmas Eve service at the Episcopal church we frequent, because Sam was scheduled as an acolyte that evening. Afterwards, close to 12:30am, he raced up to me, bleary eyed and still in his robes, and threw his arms around me announcing, “Merry Christmas!”

I drove him to his mom’s and said I’d see him and his brother in the morning. When I woke the next morning, it was snowing. I took a short walk. As I walked through the neighborhood, muted as it was by the snowfall, I remembered out of the blue, for the first time in over twenty years, that one of my English professors once introduced our class to a recording of T.S. Eliot reading his poems. For the first time in as many years, I wanted only to hear Eliot read The Journey of the Magi.

I returned to my apartment, made tea, and found T.S. Eliot reading The Journey of the Magi at the Poetry Foundation’s website. I played it twice. A day was in motion.

The boys’ mother texted that the boys were awake. Good friends texted and invited me to dinner later, an offer that provided a flush of comfort I wasn’t fully aware I even needed then. I loaded the boys’ gifts into the car. It was still snowing and that hush was only periodically interrupted by the melodic trill of waxwings dashing back and forth between trees out front.

Like the snow’s steady drift and accompanying, welcome silence, and the waxwings passing to and fro briskly overhead, this day required nothing of us. That morning, the boys demanded only that I make it to their mom’s apartment with their gifts, pronto. But the day asked nothing, save perhaps only an invitation that we live into the day we were given. There was no script, no prescribed agenda, no long ago-ascribed roles, no demands to be anywhere specific. Not even any clues for how to proceed with the day. The day only unfolded. As perhaps a good and most memorable day may wont to do – “without calculation,” to borrow from Rilke.

In that way, this Christmas was a lot like writing, like starting a new story. As with composing any new story, the writer plays a critical part in its unfolding. But so much in the details and what happens is left to mystery, too. So much so that, as with any story’s beginning, you have no idea, no clear sense of how any of it will end either. Taking that plunge, then, can often prove frightening, or at least initially a little intimidating.

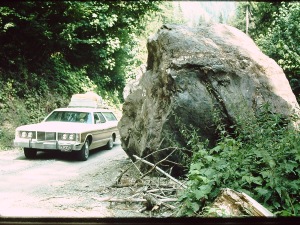

But in that flow, in the quiet stream of unfolding and unknowing yesterday, the whole birthing of the experience proved at moments quietly thrilling and then also terrifying. In that way, the day also resembled the landscape in which we daily find ourselves piecing together our lives, our family – a striking landscape, and a place that my sons know only as home.

I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.

I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.

kennels and sending silk wisping into the air. The husks ended up in the compost pile and the ears ended up in a pot of boiling water.

kennels and sending silk wisping into the air. The husks ended up in the compost pile and the ears ended up in a pot of boiling water.

g for families and forced into fruitless hard labor by a nasty overseer, Ms Hannigan, who sloppily drinks gin in her bathtub. At the end, Daddy Warbucks steps in to love and care for Annie and all is well. (Or so I remember.)

g for families and forced into fruitless hard labor by a nasty overseer, Ms Hannigan, who sloppily drinks gin in her bathtub. At the end, Daddy Warbucks steps in to love and care for Annie and all is well. (Or so I remember.)