When my mother was pregnant with my older sister, she was a visiting nurse. She drove around Aurora, Illinois in her blue Plymouth Horizon, stopping at the Dairy Queen drive through on the way home from work. She’d slurp banana milk shakes while listening to the instrumental theme from St. Elmo’s Fire.

While pregnant with me, she chased around my toddling sister. She exercised weekly at a local Christian workout class called “Believercise.” That is, until mom lunged too far, causing significant bleeding; the doctor ordered at least a week of bedrest. She had to pee in a bucket, another reason she’s the best mom of all time. In her third trimester, she survived summer days by scarfing down dripping slices of watermelon, a fruit I still consider to be one of my favorites.

There’s something sacred and terrifying about the way babies go wherever their mothers go. They eat the same foods, hear the same noises, and even pump the same blood. They can benefit or be harmed from the womb they inhabit, which is why pregnant women aren’t supposed to eat Subway or drink cocktails. Now that I’m pregnant, I worry my tiny has been anchored to a sinking ship.

You see, I’m not the best at being pregnant.

For half my pregnancy, my body rejected prenatal vitamins. I either vomited them up in fits of sweats and shivers, or they seared my esophagus with heartburn, fighting their way down the digestive tract. Everyone offered solutions, chewables, more organic options, and even a liquid green sludge that needed chased down with orange juice, but all produced the same result.

My first trimester, I survived on a diet of brown sugar Pop Tarts and Barq’s root beer. When I tried to joke with others about my nutrition free diet, they looked at me like a candidate for a morning talk show featuring teen moms who aren’t fit to be mothers. Giving nervous laughs, their countenance seemed to ask, “should you be joking about this?”

People ask if I’m excited, and I choke out the right kinds of answers. When I was younger, I pictured myself wearing pregnancy like a veil of honor, rosy cheeks and a delightful little bump showing under a flowy peasant blouse, but it turns out, I’m not the glowing kind of pregnant.

Some days I’m a nauseous, sweaty animal, sprouting a new layer of acne on my back; on these days, it’s hard to put how I feel into a pleasant statement. Instead, I lead with my signature defensive humor and make offhand comments about the anti-depressants that I continue to take while pregnant. “I would drink an occasional glass of wine, but I figure the baby already gets the Zoloft,” I say with a wink and a nudge.

This punchline hangs in the air for a few moments of painful silence before I try to reel it back in, “but you know, the doctors are monitoring the baby, and I got a special ultrasound, and…” This is when the nice person who asked me about how I’m feeling smiles through anxious eyes and clenched teeth, nodding their head to try and keep things polite.

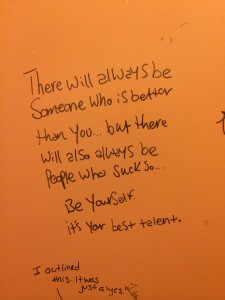

But among all the things that I know I’m already doing wrong as a mother, I’ve come to enjoy bringing the baby to the places I go. I may not do great with leafy green veggies, but my baby will grow on laughter.

My baby’s momma is a comedian. I perform in Chicago as a comedic improviser, staging twenty five minute pieces with seven to nine teammates. My three teams perform at several different theatres around the city, which averages out to two or three shows a week.

I take her with me to the bar for a drink with my teammates after a tough show with low audience attendance, trading in my gin and tonics for Shirley Temples and diet Roy Rogers. She gets the consoling pats on the back my castmates offer me, and I imagine they reverberate through my body and hit her like a wave of Vitamin D.

I take her on the stage to the sound of a quickening slow clap, which she must think is for her. Receiving biweekly applause has to be good for brain development. She goes with me into rehearsal rooms where we shriek, snort, and guffaw at each other’s moves. She’s the unseen tenth player on stage, kicking to be noticed during my scene work. I often hold my belly when I laugh, as if to make sure we’re both awake to the blessing of these joy filled spaces.

She is with me when we’re the only women on stage. As my body changes to hold her growing form, we shapeshift into diverse characters with their own points of view and treasure troves of specifics. On one night, I played a petite daughter stowed away in her father’s suitcase. I crouched low, tightening my body into a ball to simulate the cramped quarters and the baby tucked in to the warm curve of my body.

When I worry about the way my depression must seep into the womb, tears dripping through the umbilical cord and sorrow carried through my bloodstream, I revel in a night where I’m out late at a cabaret table, watching my heroes and friends on stage. Many of us are deeply sad people, but for a night, we are artists and poets who have discovered the hilarious underbelly to the tragedy.

So I’m glad that as my baby grows to the size of various vegetables, that she is growing up with laughter, that her adopted aunts and uncles are some of the funniest people in Chicago.

When I fail in so many ways that I lose count, I know the baby must know well the vibrations of her mama’s laughter, punctuated with my drawn out snorts and the fog horn blats I let out when laughter catches me unexpectedly.

I cherish this special time when I take the stage with a tiny teammate. As my friends and I wait in the wings to make our entrance, we participate in the ritual of assuring one another, we’ve got each other’s backs. I place my palms over my growing belly and say to my girl, “We’ve got this WIlla.” Together we laugh and make others laugh, and for a moment in time, we have everything we need.

***

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.