Dirty towels are stacked on the seat of my walker. An empty coffee mug, water glass, two rolls of toilet paper, and a bottle of Windex are perched on the top towel. The walker is equipped with handlebars; brake lines run from the handles to the wheels. After releasing the brakes, I roll from master bathroom to bedroom. Books, file folders, and black garbage bags, fat with fifteen years of receipts to shred, occupy a corner. I sweep a lonely group of monthly bills ready to be paid from my dresser into a grocery bag, loop and tie it around a handle.

Steering with one hand and steadying my load with the other, I turtle down the hallway. Bath tissue goes to the guest bathroom. I roll past the den into the kitchen. Coffee mug and water glass join the breakfast dishes in the sink. Sticky spots on the floor cause me to cringe, but cringing is followed by dramatic sighing. In my best Scarlett O’Hara voice, I say aloud to nobody: Tomorrow is another day.

Curving around the corner, I enter the laundry room, only to become entangled with my ironing board—it’s the kind designed to store in the wall, but never stays stored in mine. I encourage the walker to duck under the board, pulling, pushing, jerking, and yelling. I’m stuck. Blue liquid spatters from the fractured spray top of the Windex bottle as it smacks the hardwood floor. Like a basketball player trying to hit multiple shots, I hurl the towels one by one toward the rim of my top-loader washing machine. I’m zero for ten.

My orthopedist glances down at the floor as though he’s taking time to gather his thoughts to convey unpleasant news. He looks up and says: “There’s nothing else I can do for your back. Curves greater than sixty degrees (off center) will most likely deteriorate one degree yearly, so in ten years, you can expect greater pain and disability.”

My S-shaped spine glares at me from an X-ray film illuminated by light. He continues, “I don’t do adult scoliosis surgery, so I think it would be best for you to see the neuro man here in town who can follow you and determine if you need surgery now. And help you better manage your pain.”

Since I was twelve years old, I’ve had multiple visits—visit sounds pleasant and benign—to orthopedists and physical therapists. After forty years, you’d think I’d be used to hearing state of my spine speeches. Today, all I hear is finality: “There’s nothing I can do for you…”

*****

“Your spine is curvy,” says this short, curly-haired neurosurgeon dressed in a coat with buttons straining over his paunch.

I can’t suppress a giggle. “My husband says I’m curvaceous.”

“Oh, that’s a good one.” We hit it off like two vaudeville comedians.

While looking straight at me, he asks about the severity of my pain on a scale of 1-10. He takes my hand and helps me descend from the exam table. I stretch and try to touch my toes as he runs his fingers along my spine, tracing from top to bottom, a squatty, fat “S.”

“If you are functional, I prefer not to do surgery until you are well into your sixties. You can’t fool around with the spinal cord. We must ask: when do the benefits outweigh the risks?

I nod, listening. He continues, “I could make you straight—straight in your coffin.”

*****

I sit on my walker to rest after preparing dishes for our Thanksgiving meal. As I stare across the kitchen island’s glossy, black surface, I think of my grandma who had a holiday menu a mile long. My menu has shrunk from feast to famine: one meat, two vegetables, rolls, and store-bought dessert. I feel deficient. My dead grandmother is disappointed in me.

I am a mess. My vertebrae are like a stack of plate-spinners’ china: swaying, unbalanced, ready to crash. My body will not move like I want it to. Thoughts are scattered in my mind. My prayers bounce between Help! and Thank you!

I can, in most moments, stash negativity in a dark corner of my mind and will myself through the messiness of life. But, today, I am depleted. I’m taunted by sunlight streaming across the floor, highlighting dried splats of liquid. Crumbs fill cracks between the floor planks.

Then, I glance up and see light and shadows dancing with the colors of glass in my kitchen window. I laugh at myself. Oh, the absurdity of letting specks of dirt impair my vision.

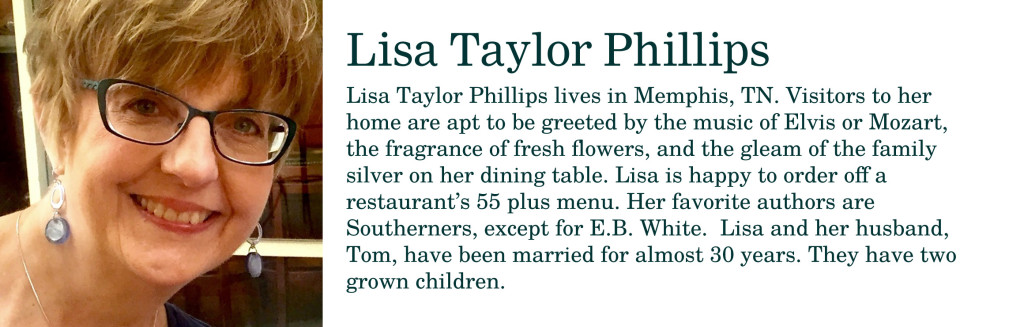

Images by Lisa Taylor Phillips

Images by Lisa Taylor Phillips