Nine months after my college graduation, I find myself living with my parents, looking for work, trying to write more frequently, de-cluttering my room, and generally freaking out about life. It is a time of uncertainty, a time that requires more patience than I have.

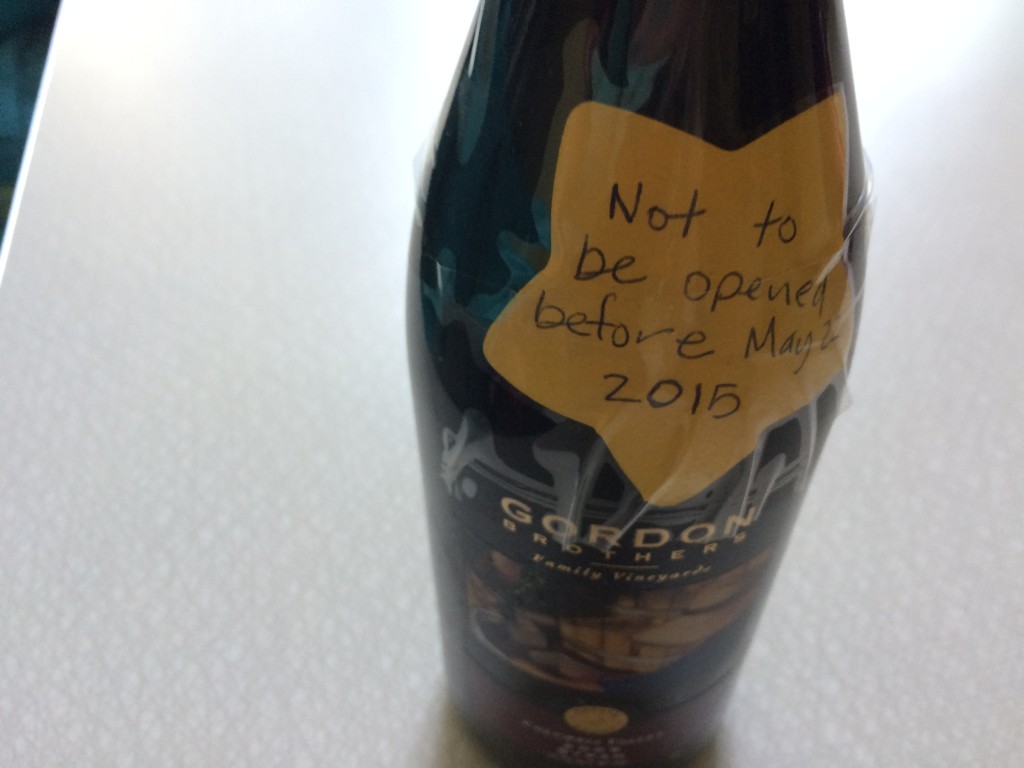

The lamb stew I am cooking for St. Patrick’s Day takes patience, too. Lamb—trimmed of excess fat and cut into 2-inch cubes—simmers with beer, some spices, and broth for at least an hour before I can add the cubed potatoes and sliced carrots. I start early in the afternoon so that the stew will be ready for my family’s 6 o’clock dinner hour. As it cooks, the stew fills the kitchen with a meaty smell. Its taste, when we finally sit down to dinner, is rich, with a hint of thyme and a ghost of wheat from the beer. My family’s silence indicates their approval.

Deciding to make lamb stew was not so much a whim as a nostalgic gesture to the weekend I spent in Ireland three years ago. It was the end of my semester studying abroad. Four girlfriends and I had arranged our flights to stay over in Ireland for the weekend. After a jaunt to Galway, the Cliffs of Moher, and the shrine at Knock, we returned to Dublin for a farewell dinner to Europe. We chose what the hostel employee told us was the oldest pub in Ireland—The Brazen Head—partly for its history and partly because it was only a short walk away. A waitress seated us at a battered wood table in the pub’s squashed and dimly lit interior.

Four months abroad had felt like a lifetime; we were ready to return to American soil and our families. Yet, at the same time, we were overflowing with the exhilaration of seeing the world, of being young, of having friends, and of being more or less carefree. We ordered Guinness and raised a glass: to friendship, to Ireland, to life.

Four months abroad had felt like a lifetime; we were ready to return to American soil and our families. Yet, at the same time, we were overflowing with the exhilaration of seeing the world, of being young, of having friends, and of being more or less carefree. We ordered Guinness and raised a glass: to friendship, to Ireland, to life.

When the time came to order our food, I knew I had to try a truly Irish dish. I chose the lamb stew. Ladled into a wide-rimmed, white bowl, it came with a scoop of mashed potatoes floating on top. Crusty brown bread was served on the side, slathered in butter, which of course I dipped in the stew, soaking up all of its delicious gravy. My friend, Allison, also ordered the lamb stew and together we reveled in its heartiness, while the other girls enjoyed beef and Guinness stew, another Irish favorite.

Stew, in all its forms, although hearty and flavorful, is a rather unremarkable dish. What was it about the Dublin lamb stew that captured my attention so that it stands forth in my mind as a dish worth recreating?

I felt whole during that weekend in Ireland. Now that I had seen places that before I had only read about, the world seemed smaller. Anything was possible. I could go anywhere. I could meet anyone. I could do anything.

Perhaps, subconsciously, it is that feeling of potentiality I am seeking to recapture as I cook lamb stew for my family this St. Patrick’s Day. A bubble of hope rises in my heart like those that rise to the top of my stew as it breaks into a gentle, rolling boil. Anything is possible.

* * * * *

“Dublin Lamb Stew” is by Stasia Phillips, a writer and amateur cook who loves a delicious bowl of stew once in a while. Studying abroad in Austria for a semester opened her eyes to a whole world of flavors that she is slowly incorporating into her cooking repertoire. Stasia draws inspiration for her writing from nature, good books, her faith, and hazelnut coffee. You can find her blogging at “Cold Hands, Warm Heart.”

“Dublin Lamb Stew” is by Stasia Phillips, a writer and amateur cook who loves a delicious bowl of stew once in a while. Studying abroad in Austria for a semester opened her eyes to a whole world of flavors that she is slowly incorporating into her cooking repertoire. Stasia draws inspiration for her writing from nature, good books, her faith, and hazelnut coffee. You can find her blogging at “Cold Hands, Warm Heart.”