Somewhere deep where we have no program our next discovery lies.

– William Stafford

I don’t remember what I expected or wanted that evening in 1992, the night I first bumbled into J.C. Dobbs. I imagine I was too embattled by nerves and anticipation as I entered the venue to hazard any expectations. Back then, I hadn’t ventured solo into Philadelphia, hadn’t pushed past the border of my neighborhood at the city’s edges with any frequency. The World was out there, and all the dreadful, dangerous, hot bloodlust associated with it, and we’d come to understand early on – falsely – that to keep close meant we could stay safe. And while I had seen the bar area at different restaurants before, until that night I had only ever been inside one actual, real bar. That first time, a couple years earlier, I was only let in to see the show if I wore a wrist band and my dad accompanied me. Somehow, I managed to convince him to serve as my chaperone.

Dobbs was smaller than that place. When you walked inside, it looked like you were staring down a dimly-lit, roofed alleyway. The stage rested at the center of the small room and while all the band’s gear appeared onstage, it was hard to imagine how more than one person could fit up there. From the entrance at the back of the bar, the stage resembled the narrow plank of a pirate ship. An absurdly thin hallway curled past the right of the stage, leading to the bathrooms and a stairwell reaching to the second floor.

Dobbs was smaller than that place. When you walked inside, it looked like you were staring down a dimly-lit, roofed alleyway. The stage rested at the center of the small room and while all the band’s gear appeared onstage, it was hard to imagine how more than one person could fit up there. From the entrance at the back of the bar, the stage resembled the narrow plank of a pirate ship. An absurdly thin hallway curled past the right of the stage, leading to the bathrooms and a stairwell reaching to the second floor.

My folks had caved that evening and allowed me to drive the Country Squire – that faux-wood-paneled beast – down to South Street, though not without reminding me that someone had recently been shot in that part of the city. My mom, discomfited that I intended to make the journey to South Street solo, asked more than one time if I really had to go down by myself. But who would I have asked? My hometown friends had all returned to their different colleges. I was still languishing at the community college, resigned to living at home and working – part-time at K-Mart, part-time as one of the church janitors – absolutely clueless about where to direct my energies, or how to put the next steps of my life in motion, much less know what to be when I grew up.

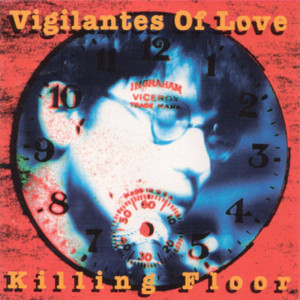

I can’t tell you today where I first heard of the Killing Floor album, or how I even came into possession of  the record on a blank cassette. I only recall now that the magic words, “Athens, Georgia” and “…co-produced by Peter Buck” appeared in the press around the album – news that immediately yanked me into its orbit. At that time in my life, any and all association with R.E.M. compelled an urgent drive to seek out an artist’s material. Any artist that stood even a mild chance of doing to my heart and skin what R.E.M. albums did to me was worth a try. In fact, that’s what I must have sought out of this experience, from this evening’s nerve-addled journey: I wanted these ambassadors from R.E.M.-country to bring me to life in real time; I wanted in a live setting to feel the red clay of Georgia on my skin, to feel something similar to what Athens’s luminaries could do to my loneliness through my headphones.

the record on a blank cassette. I only recall now that the magic words, “Athens, Georgia” and “…co-produced by Peter Buck” appeared in the press around the album – news that immediately yanked me into its orbit. At that time in my life, any and all association with R.E.M. compelled an urgent drive to seek out an artist’s material. Any artist that stood even a mild chance of doing to my heart and skin what R.E.M. albums did to me was worth a try. In fact, that’s what I must have sought out of this experience, from this evening’s nerve-addled journey: I wanted these ambassadors from R.E.M.-country to bring me to life in real time; I wanted in a live setting to feel the red clay of Georgia on my skin, to feel something similar to what Athens’s luminaries could do to my loneliness through my headphones.

Maybe you can remember a time when you were someone’s biggest fan, too. Maybe you can identify on some level with my admittedly-juvenile adoration, devotion, and logic here.

***

I don’t remember how long I stood in the back of the bar that evening before the band I had come to see took the stage. What would they even look like? I had seen the album cover in a magazine, so I knew the lead-singer/songwriter wore glasses.

I can’t remember now how long I stood in the shadows in muted, wide-eyed anticipation.

Waiting.

***

Did I emerge hours later? Days? Moments?

Whatever the case, spilling out the door of JC Dobbs and back onto South Street, I may as well have stumbled out of the wardrobe from Narnia. For all I knew, years could have passed on the other side of the venue’s door.

What had I just witnessed? Lived through? No – not lived through. I had survived. And just barely.

The four members of Vigilantes of Love had not performed on the bar’s narrow stage that evening so much as “Gone Off.” Walked onstage, picked up their instruments, and then exploded like a malatov cocktail in a fireworks factory.

I’d never seen anything like it.

True, I had not seen much until that time in my life.

But how did they pack up and drive away after that anyway? How did they sleep?

And, dear Lord, who in the world let them get away with that?

At the same time, Bill Mallonee and company were not even doing a job that night – or on many of the other nights I would watch them over the years that followed: It became apparent that whenever the Vigilantes of Love walked onstage and leaned into the evening and their songs, they set to the urgent task of saving their lives, and STAT. And in their excruciating, vulnerable, death-defying, Evil Knievel approach to rock and roll, they converted me to something. But to what exactly? It’s taken me at least this many years living with that question to arrive here: I still don’t have an answer for you.

***

I found my breath and rose above the evening’s surface. I knew only one thing as I fumbled around for my keys outside: Everything I’d heard until then – which was admittedly not much from within the bubble, the subculture of my origins – proved a gelatinous, soft-butter imitation of men daring to pretend they played rock and roll. Whatever other bands I had seen were doing, they’d left their turning signals on. They drove through songs too carefully, with a donut, hazard lights blinking. At best, other bands onstage resembled zombies craving their own souls; ghosts hungry for the warmth, the heat of their own flesh.

***

I have seen many concerts since that night. Some of which have perhaps rivaled or surpassed that lone 1990’s bar-burner. I couldn’t say.

But I was a walking matchbook right then. And lonely. Adrift at sea. No compass. If you’d held my hand under starlight, played me your favorite song, or asked me to tell you the deepest desires burdening my heart in those days, we likely would have exploded into a cosmic supernova together.

That night, four men came dangerously close to setting me ablaze. And I do know – I can tell you – there were sparks that evening.

And on some nights, I can still smell the smoke.

(xoxo Bill Mallonee, Newt Carter, David LaBruyere, & Travis McNabb…)

In memoriam, Robert Newton Carter, 1966-2015…RIP

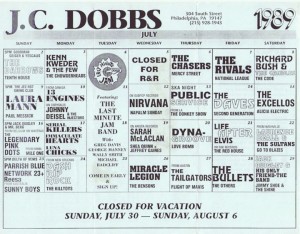

Pic of a 1989 schedule of shows at J.C. Dobbs in 1989 found online…you’ll notice a couple acts here went on to become household names.