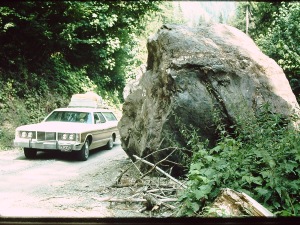

Every Saturday afternoon our church gymnasium transformed from a basketball court or hockey “rink” into a sanctuary. In fact, our church was little more than a gymnasium with a maroon floor and a few offices with thin carpets around it. If our church youth group was in charge of church set up in the afternoon, we’d sometimes play hockey in the morning, go out for lunch (Wawa hoagies were my personal favorite), and return to help with the set up.

However, some Saturday afternoons I joined adult home groups and Sunday school groups at church as they hauled out racks of chairs manhandled the wooden platform into place. I gravitated to the large wet mops that followed the dust mops along the floor, leaving a smooth, shining surface before we did the heavy lifting with the chairs and section dividers.

I’d also tag along with the church janitor if he ever needed a hand. I’d become so accustomed to helping out that when he went away on vacation, he hired me to take over for him. I brought along two friends who split the pay but made the work go much faster. This earned me a key to the church while still in high school.

I’d also tag along with the church janitor if he ever needed a hand. I’d become so accustomed to helping out that when he went away on vacation, he hired me to take over for him. I brought along two friends who split the pay but made the work go much faster. This earned me a key to the church while still in high school.

There’s no denying that I like a tidy space. I like things in their place. I’m that person who rearranges the dishwasher with the big plates in the back, small plates in the front, bowls in the top center, and glasses on top sides. I’m the sweeper and the arranger of stuff in our home for sure, and I embrace that role. That isn’t all of it.

My high school years were tumultuous and divisive. Life at home was full of highs and lows. I didn’t just find friends or community at this Baptist church down the road from our house. I found a peaceful sanctuary. I wonder if I instinctively knew that I could relax in my church. It didn’t matter if I was listening to a sermon, playing hockey, or mopping the floor.

Looking back, I can see that I needed a place to be at rest, and when it feels like a divorce is tearing everything at home to pieces, it can be quite restful to set up a gym with 400 chairs in a semi-circle with a group of friends—or strangers. It doesn’t really matter. For some reason there’s nothing like walking into a dusty, chaotic gym and turning it into a clean, orderly space with carefully arranged rows of chairs and a backdrop of fake plants.

Mind you, I wouldn’t have complained if my church had sped up its transition into more contemporary music. In retrospect, the most relevant and relatable aspect of my church was the way I always felt welcome and at home. I’m sure our janitor could have worked a little faster without me tagging along, and I’m sure those set up crews didn’t need me to mop or set up chairs.

They didn’t need me, but they always welcomed me.

I just had to show up ready to use a mop or a move a few chairs.

I’ve read a lot about children who have parents go through a divorce and how they need an anchor. They need a stable place or relationships where they can feel a sense of peace and stability. For me, it was my church. My church was far from perfect, but for a season when I needed an anchor, it provided one when I needed it the most.

*****