My grandmother assumes her regular position at the head of the table, a spot she reserved for herself after my grandfather passed away.

As the youngest of the family, I sit in the spot right next to her. It’s a privilege that I’ve proudly carried into adulthood. The ceiling fan is running, creating a whirlwind of mucky, humid air. It’s always humid in India, but it was summertime when I visited that year, so the humidity was more like a sweat-fest. The fifth floor of the apartment building invited some cool, coastal breeze every now and then, but it was never strong enough to drive away the mugginess.

My grandmother, or mummy as I call her, opens the container of fried plantains, a treat she got while I was out earlier that day. I smile – she remembered that I loved these when I was little.

I take a bite, sip the chai, then smile. Even though I was only visiting for a couple of weeks, it didn’t take much for that muggy apartment to feel like home. Mummy knew how to make it home for me.

I slowly start to peel off the battered outer shell. It was sweet, crunchy and drenched in oil, and oh my gosh, did it taste like heaven. I look over to find mummy doing the same. We catch each other’s gaze and chuckle.

I slowly start to peel off the battered outer shell. It was sweet, crunchy and drenched in oil, and oh my gosh, did it taste like heaven. I look over to find mummy doing the same. We catch each other’s gaze and chuckle.

“I forgot that you like the outer shell as well!” I exclaim, quite amused.

Mummy doesn’t reply and continues eating. But she doesn’t bother hiding her smile.

Other than our love for fried plantains, we don’t have a lot in common.

Mummy thinks girls should know how to cook, garden, sew, brush their hair, make their beds, and walk properly. I think that women should do whatever the heck makes them happy (for me, this does not include cooking, gardening, sewing, brushing my hair, making my bed or walking like a proper lady, whatever that means). Naturally, we argued a lot over the years. Every time she would begin her lecture with “As a girl you MUST…” I would roll my eyes and suppress the urge to return my “GIRLS CAN DO WHATEVER THEY DAMN WELL PLEASE” speech.

But lately, she doesn’t lecture me. We don’t argue or bicker. We sit in silence, mostly. There are some awkward attempts at small talk, but mostly just silence.

I want to ask her to repeat the stories she used to tell me, but I cower. I’m afraid that if she tells me these stories again, that it will be the last time I will hear them. But oh, how I yearn to hear her say the words once more. I want her to tell me what she’s feeling, what she’s thinking, her hopes, her dreams, her heartaches, her delights. I wonder if she wants to hear my stories and my thoughts. Compared to what she has given me — the tales, adventures and wisdom of a life that was so fully-lived — what do I have to offer? I don’t really have much to tell or offer. And yet, I want to give her so much. Time is slipping, and I am afraid that I will never get a chance to give her something, anything.

“Do you want another one?” Mummy asks.

I shake my head and put the last piece of the outer shell in my mouth.

Mummy tears off a chunk of her outer shell and puts it on my plate.

I want to refuse and put it back onto her plate, but I don’t. Instead I offer her a smile and some unspoken sentiments.

She doesn’t acknowledge it, but I can tell that she’s received it. She has heard me.

* * * * *

“Grandmothers and Fried Plantains” is by Leah Abraham. Leah is a storyteller + writer + journalist + creative + empathizing romantic + pessimistic realist + ISFP + Enneagram type 2 + much more. She lives in the Pacific Northwest, loves the great indoors and hates to floss. Also, she is obsessed with Korean food, sticky notes and her dorky, immigrant family. Leah occasionally blogs at www.leahabraham9.wordpress.com.

“Grandmothers and Fried Plantains” is by Leah Abraham. Leah is a storyteller + writer + journalist + creative + empathizing romantic + pessimistic realist + ISFP + Enneagram type 2 + much more. She lives in the Pacific Northwest, loves the great indoors and hates to floss. Also, she is obsessed with Korean food, sticky notes and her dorky, immigrant family. Leah occasionally blogs at www.leahabraham9.wordpress.com.

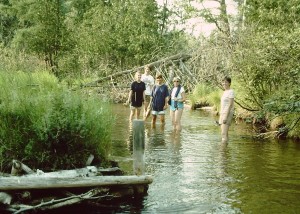

The photograph of fried plantains used in this post was taken by Rahul Sadagopan.