“…but don’t you think the gazebo looks a little bit small?” The voice of our Austrian tour guide settled comfortably at the top of the treble clef. Saccharine as Salzburg’s famous Mozartkugel, this woman might as well have been a recording playing from an MP3 player hanging from a lanyard around our necks.

“How could they do the sixteen-going-on-seventeen dance here?” She jutted her head forward, the rest of her body remarkably stiff.

At this point in the tour, I could see where her query was going. Similar rhetorical questions had lead to the revelations that the front of the Von Trapp family home was a different property than the back of the house, that we couldn’t get to the exact spot where the opening had been filmed, and that the free place to stay in the downtown was in fact the city’s prison.

While the Alps were, well, the Alps, just about everything else from the movie was a jumbled amalgamation of buildings, Hollywood soundstages, and private properties that we whizzed past on the tour bus.

When Josh and John Mark had invited me on their European adventure, the Sound of Music Tour had been my one stipulation, my “must-see.” I promised to trek with them to stare at the outside of houses Dietrich Bonhoeffer had lived in and to check out the East Berlin Wall Gallery despite frigid winds, but this was my stipulation—to finally embark on my musical theatre pilgrimage.

I don’t know what I thought would happen on the Sound of Music Tour. That someone would hand me an outfit made out of draperies and teach me how to sing? That I’d share in an oddly steamy Austrian folk dance with Christopher Plummer? Or perhaps that I might stomp around downtown Salzburg with a guitar case wearing a dress that “the poor didn’t want” whilst asserting my self confidence in song. If you don’t know the moments in the movie to which I am referencing, you’re missing out.

Instead, at every turn, I was discovering that my childhood favorite movie was cobbled together from scraps of Austria and the Twentieth Century Fox Studio in Los Angeles.

I laughed nervously with my travel companions hoping for the transformative experience to start at any moment, so that the boys would think the tour was “worth it.”

Worth it.

It was the rubric I applied all along our trip to Europe, a notion I’d picked up in a frugal home where each dollar spent on vacation was squeezed like a wet rag till every last drop had been extricated. It was in the way my mom read every placard at the museum and it accompanied the anxious hum in the back of our minds; we may never get to come back to this place. So we’d hover a little longer, trying to stare hard enough at our surroundings to render them meaningful and worth it…

It wasn’t just Salzburg and the tour bus piping Julie Andrews and the Von Trapp Family Singers through its speakers, it was the Holocaust museum in Berlin, and Prague, with its corridors of gift shops filled with sundry items branded with their city’s name. At each stop, I longed to feel different and romantic, and at each stop I found myself tired, or introverted, or hungry, or craving a Diet Coke.

I found myself to be the same self I was in Chicago, except disillusioned that inhaling the European air hadn’t transformed me. In Europe, as in Chicago, real life was much more embodied and much less ethereal than it was in my daydreams. The hard things about being me, about being an adult, my depression and anxiety, and even the prickly hairs that sprouted from my chin, remained.

The Sound of Music tour guide continued with her characteristic refrain, dismantling the magical world created in the film. “How could they do the sixteen-going-on-seventeen dance in such a small gazebo? Hmmmmm? That’s because they didn’t. They built a larger one in Hollywood…”

We couldn’t even go inside the gazebo, because an elderly guest had recently broken her leg trying to dance on the benches as Liesel and Ralph do in the movie. Our passion for the film was a liability to the touring company at each step, as we were reminded to keep everything at an arm’s reach.

The tour ended in the town with the church where Maria and the Captain got married. The interior of the church had been painted pink. Pink. I took an obligatory picture in the aisle of the cathedral, wanting to stomp out of the building like a grumpy toddler. I had been promised magic and instead found altered buildings and relics beyond reach.

As she was wrapping up the tour, the guide suggested we try some “crisp apple strudel,” which was sold at several shops in town for the consumption of parents who had dragged their kids on the tour and retired couples who had watched the movie premiere in theatres. At the peak of my frustration and need for air, we took our strudel “to-go,” a phrase hardly ever uttered in Europe, and went out to explore the town.

I tried to check-in with the boys to see if they resented the fifty dollars spent on the tickets, trying to distract them with impressions of the tour guide and her underwhelming introductions at every stop. Josh and John Mark felt the disappointment of the tour, but it seemed they were able to brush it off, laugh it off…

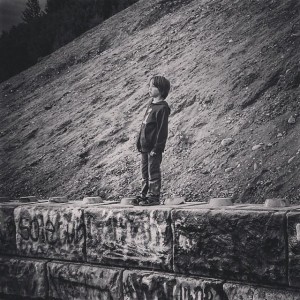

As we walked with our noisy plastic to-go boxes chasing the strudel around the base of the containers with plastic forks, we came upon the shore of a lake tucked in the mountains. It looked like something out of Middle-Earth. Long docks stretched their arms into the water and fog rested and pooled around rooftops painted with snow drifts.

It was a view similar to one in the movie, but begging to be examined on its own merits for its mountains, spiky pine trees, water smoothed as if with a frosting knife, and dissolving horizon, where the water seemed to fall off the edge of the earth in an interstellar waterfall as it disappeared from our eyesight.

Maria Von Trapp, The Grand Canyon, or the Eiffel Tower may draw us to a certain place, but the experience we have there must transcend what could be reduced to a postcard. My experience of the “Sound of Music Tour,” once let loose of my expectations, expanded to more than I could have anticipated.

The tour was posing on the steps where Do-Re-Me had been filmed, but also the hostel we trekked to in the dark along steep gravel paths that seemed more like landscaping than legitimate passageways. It was feeling pretty in my vintage dress cinched in at the waist as we snapped hundreds of pictures at the mystical docks. It was the strudel in crinkling plastic containers, and even the monotone tour guide who disappointed my expectations at every turn.

The tour was a means to an unexpected end, as each stop begged to speak for itself and show us why it is special, the hills not so much alive with the sound of music, but asleep under blankets of snow.