I know I’ll make it back

One of these days…

Where the cups are cracked and hooked

Above the sink

And a cracked door moon

Says I haven’t gone too far

– “Via Chicago,” Wilco

What is it that proves so timelessly compelling about an unknown place – and especially the distant, the faraway – the Not Here Where I Am Right Now? Maybe there’s an anthropological study or psychological classification for this phenomenon. Perhaps Lonely Planet or Rick Steeves have a term that adequately summarizes our thirst for going someplace thoroughly unfamiliar, for getting a little lost, for stumbling through a foreign anywhere with only a select handful of phrases, and eating whatever seems most intriguing or unlike the foods found in the places we’re from. “Wanderlust, dummy,” you could say, but that’s not what I’m getting at – or, it’s not only that. Wanderlust, to me, feels too temporal, too casual to properly describe the specific longing I’m describing. What do I call that spirit that comes to life when I’m huffing away on the Stairmaster at Planet Fitness and Anthony Bourdain is on TV sipping a steaming liquid from a delicate ceramic cup, or eating meat or cheese from a place where everyone’s skin is darker than his? In those moments, I want to know those people and that place, but I also know the likelihood of deeply or intimately doing so is highly unlikely.

I’m curious on one hand because I’ve recently become worried, wondering if I, over the past twenty years, unwittingly traveled and “adventured” myself into a corner. Rather, in making a lot of my life one fascinating backdrop or living experience swiftly following another, I now find myself at a bewildering impasse: This year marks my tenth as an Alaskan resident, which means I’ve lived here longer than anywhere else save for my state of origin, Pennsylvania. And despite an active engagement in Alaska over the course of that decade, I still find myself feeling oddly far-flung, a bit adrift, “a stranger in a strange land,” and frequently out of place in a location that my two sons – both born and in love with their lives here – fully consider and embrace as home.

a bit adrift, “a stranger in a strange land,” and frequently out of place in a location that my two sons – both born and in love with their lives here – fully consider and embrace as home.

Under my love of the wildly unknown and the thrill instilled by journeying to new places, I’m now finding another form of longing, and in recent years it’s proven a deeper, heavier pull than the passions that lured me towards a tireless series of fascinating locations and situations in previous decades. In simplest terms, I think mine proves a longing that all of us to one degree or another carry for “home.” And yet, I worry that naming it as such reduces it to a pouty, Dorothy Gale-by-way-of-Judy Garland type of pining. Either way, however, it’s perplexing that I would experience these conflicted feelings while occupying the same location on Earth where my children feel so utterly present and at home.

Meanwhile, “home” doesn’t often seem a very “sexy” or hot topic to bridge in conversation. It’s not a subject that gets many people excited, unless you’re discussing the purchase of an actual, physical “house,” or watching a cable reality show where a couple’s house is about to be remodeled or transformed from Ordinary into a palatial estate. Otherwise, it’s probably not a topic that will really charge a conversation the way “travel” or living abroad do when you’re trying to make friends or identify yourself among new acquaintances at a party. Where we’ve been and what we’ve done or seen tells others something significant about who we are (or, who we think we are) in a way that trying to discuss remaining still or feeling content rarely, if ever, will.

When I make a reference, for example, to “when we (my then-wife and my boys) lived in Japan,” something sparkles in the listener’s eyes, or a smile swiftly dances across his or her face. I imagine they, like I used to do, entertain a swift, thrilling montage of koi ponds, teahouses, manicured gardens, and exquisitely designed pottery and luxurious foods. At one time I strongly identified with and entertained that same montage.

And yet, I highly doubt anyone recognizes by referencing “when we lived in Japan,” a part of me bristles inside. In fact, I sometimes feel sheepish sharing that we did – it feels rather like a misstep in the pace of a conversation. Nowadays, it’s almost as if I admit I lived there to a listener. There’s no romantic indulgence in revealing it, no bragging rights. Rather, a part of me goes a little limp inside. And oftentimes, saying I live in Alaska has felt this way, too. And I never imagined going into either of these situations that I would one day feel this way.

With Japan, I imagine a big part of this is that it’s the place where, over the course of a few days my sons’ mother and I briefly feared that our one-year-old might die. It’s also where his mom and I one year later realized and faced the hard cold truth and acknowledged aloud that our marriage was, in fact, dead.

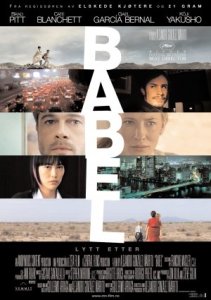

Rather than an exotic, storybook fantasy, our experience more closely resembled that of the characters in the film Babel, many of whom acutely wrestle with a 21st-century specific form of displacement and confusion related to being out of place, far flung from any idea or notion of home.

I was reminded of all of this the Tuesday before Thanksgiving a couple weeks ago, when my youngest, now six, received a visit from the latest flu monster currently making the rounds up here.

A friend had a week or so earlier invited us to dinner with his extended family at their log home in a town three hours north of Anchorage. I looked forward to fleeing the city for the holiday, but a restless night with a boy battling a 103F temperature in the mornings leading up to Thursday found me a little beside myself, brainstorming a possible “alternative” Thanksgiving if we were possibly stuck at home.

I had done very little shopping, which is to say none at all, aside from purchasing some odds and ends for the table of the friends’ home where we were intending to spend the holiday. I was definitely turkey-less, and I didn’t even have a single can of the gelatinous, can-shaped substance we call cranberries. I couldn’t help imagining that if Matt’s health dictated that we stay in Anchorage, this year would go down in my ten-year-old, Sam’s journal as the year we ate turkey club sandwiches at Denny’s.

In hindsight, I see that my panic was fueled by a clueless, single father’s blend of confusion and distress around both properly caring for a sick boy with the flu and a 103F fever, as well as having no grounded family traditions in place up here for possibly observing the holiday. The latter realization was compounded by the knowledge that we also have no immediate or extended relations anywhere nearby – nowhere, in fact, within a twelve-hour flight across the country. Which meant, too, that I had no family to call on for assistance for the Tylenol I was out of at 1am, or family to crash with on the holiday or to send Sam to if I were stuck home with Matt, on a holiday during which time we customarily celebrate and gratefully reflect on family and our ties that bind.

I’ve sat in a remote Japanese village after the orange harvest eating horse meat and drinking a clear liquor made from sweet potatoes that I’m sure must have shared chemical properties with space shuttle fuel, all while knowing only a handful of stock phrases you could pick up from watching Lost in Translation.  I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.

I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.

But nothing – I swear to you, nothing – in my life has felt more truly foreign or alien to me, honestly, than the terrain of single parenthood these last three years, and nowhere more so than in the helplessness that springs to life when the children are sick, or during the holidays when – minus the grounding of roots or traditions – I’ve wondered where to orient the three of us.

And don’t get me wrong – I do treasure the sum of my adventures. They make for rich memories, and mine’s proven an undeniably privileged way to spend one’s young adulthood. However, as I sat at my son’s bedside, anxiously scrolling WebMD.com on my laptop for advice on how to care for a child’s flu and fever that Tuesday evening before Thanksgiving, as he writhed and his breath scraped along his throat and through his nostrils, I also wondered about what I may have neglected or failed to consider during my years exploring distant places, gathering mostly only experiences in everywhere and anywhere entirely unfamiliar…

Although I didn’t venture out on my own at first, soon I grew a bit more brave (or perhaps just desperate). Although I worried about getting lost, I walked the blocks to Queen’s Way, slipping into a Spar I’d visited earlier in the trip with fellow students. I purchased a samosa, some decaf PG Tips (the tea my mother drank at home on special occasions) and a single piece of baklava.

Although I didn’t venture out on my own at first, soon I grew a bit more brave (or perhaps just desperate). Although I worried about getting lost, I walked the blocks to Queen’s Way, slipping into a Spar I’d visited earlier in the trip with fellow students. I purchased a samosa, some decaf PG Tips (the tea my mother drank at home on special occasions) and a single piece of baklava.

I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.

I’ve drifted through a Russian village meat market and stood slack-jawed watching a toothless man butchering a pig – cigarette dangling from his mouth, no shirt or gloves – in a way that would no doubt cause reps from both OSHA and the FDA to collapse from aneurysms. I’ve lived five miles deep in the woods of New Hampshire without running water all winter. Stood thigh-high in steaming piles of horse manure twenty-one miles up a mountain in Oregon, holding only a shovel and longing for nothing more than to finish the job and return to my wood-heated cabin and books a stone’s throw away.