It was the first Sunday after the election, and I wasn’t the only one who came to church in search of healing. Our congregation is many in terms of race, culture, background and class; but we gather because we were also one. One hope. One faith. One Lord. One old red-brick building facing east, perched on a hill overlooking a wide, crowded valley. Overlooking the city that is my home.

Pittsburgh, Pa. November 13, 2016. Mercifully, the sun had risen another day.

On that Sunday, I gave and received hugs, eased my body into a pew, and tried to settle my mind. Our daughters were collecting crayons and paper from the table in the back, and my husband sat close, leaning into my arm. He knew I was barely hanging on.

I sighed.

Psalm 27 filled the first page of the bulletin. Too much text, I thought. I need to sing. I was desperate to gather up the chaos inside and release it into words, notes, and vibrations. I needed our collective voices to transform some of this pain into hope.

But I had no choice. This was how we were beginning. And so, as sunlight through stained glass filled the room, I submitted to the many words.

The Lord is my light and salvation. Whom shall I fear? The Lord is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?

And I thought, Lord, would you like a list?

When evildoers assail me to devour my flesh–my adversaries and foes–they shall stumble and fall.

Or win elections. Betrayal was still bitter on my tongue.

…though war rise up against me, yet I will be confident… for he will hide me in his shelter in the day of trouble… Hear, O Lord, when I cry aloud, be gracious to me and answer me!

The psalm went on and on. And on. Together we heard it. Together we allowed it to soak in. Together we let the light crack through the stone we were using to protect our aching hearts.

You could almost hear the chisel at work: Do not forsake us, Lord–the Lord will not forsake us–Do not forsake us, Lord–the Lord will not forsake us.

Chip, chip, crack.

I believe I shall see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living. Wait for the Lord; be strong, and let your heart take courage. Wait for the Lord!

Now it was time to sing.

* * * * *

Later, during prayer request time, we shared our own words.

I know a lot of army recruits. I’m concerned that the fear and the rhetoric will lead to more deployments. These recruits–they’re great kids.

Our foundation cannot be shaken–God is still in control. God is king of kings, president of presidents. No politician has ultimate power. Don’t be afraid.

How can we have reconciliation with Christian brothers and sisters who don’t even understand why this hurts so much?

If Muslims are forced to register, we will also register as Muslims. Because Jesus is Lord.

First, we cast our votes. Now, we cast our lives. This won’t be the first time.

And, like Psalm 27, we went on and on. And on.

* * * * *

My family left before the end of the service. We had previous plans to visit my parents, who live an hour out of the city. But first, on our way to their house, we would go on a quick bike ride. It was a beautiful fall day in Western Pennsylvania, and we had wanted to try this trail for months.

But now I was nervous.

As we drove north, the Trump yard signs multiplied, and my stomach tightened. Paranoia surfaced. Why had my husband insisted on wearing his “Black Lives Matter” t-shirt? Would someone say something disparaging in front of the girls? Or worse? We would be in isolated places on the trail. What if someone tries to hurt us?

I had one comfort–it was cold. My husband would have to wear his flannel over his t-shirt. We could blend in. None of us had dark skin, or wore a hijab, or seemed ‘other’ in any other way. No one would know who we were and where we came from.

And that quickly, I forgot who we were and where we came from.

* * * * *

The other day a friend said to me, “There are people who are deeply invested in the divisions in America.” This didn’t make sense at first. Aren’t the deep divisions our problem? But then I realized–it is the divisions that keep us safe.

As long as my husband wears his “Black Lives Matter” t-shirt in the city and his flannel in the country, we will be safe. As long as we vent our frustrations about the election with like-minded friends, no one will challenge us. As long as we pray with people who feel our pain, we can comfort one another.

Now. There’s nothing wrong with comfort, venting, or self-preservation. But we can’t stay there. Somehow we must find a way to bring our whole selves into the scary and uncomfortable places. We must listen. We must speak, somehow, in a way that can be heard across the divides.

We must learn, and learn again, to love more than we fear.

Last night I wrote out the text of Psalm 27 and posted it by my bathroom mirror. It is a reminder. A clue. A signpost on the way to hope, which I might be needing in the days to come.

The Lord is my light and salvation. Whom shall I fear? The Lord is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?

No one, Lord. No one.

but her sister had already dropped her pants and planted herself on the toilet. I glared at her, “Just hurry up, okay?” My youngest recovered quickly, as she does, and crouched on the bathroom floor–she wanted to see the shoes of the person in the next stall. “Stop it!” I warned, “and don’t you dare touch that floor! I told you bathroom floors are dirty!”

but her sister had already dropped her pants and planted herself on the toilet. I glared at her, “Just hurry up, okay?” My youngest recovered quickly, as she does, and crouched on the bathroom floor–she wanted to see the shoes of the person in the next stall. “Stop it!” I warned, “and don’t you dare touch that floor! I told you bathroom floors are dirty!” We are attempting to raise our children as followers of Jesus–thoughtful, compassionate, joyful people whose lives are defined by loving God and neighbors. We pray for God’s spirit to fill them, to make impossible things happen.

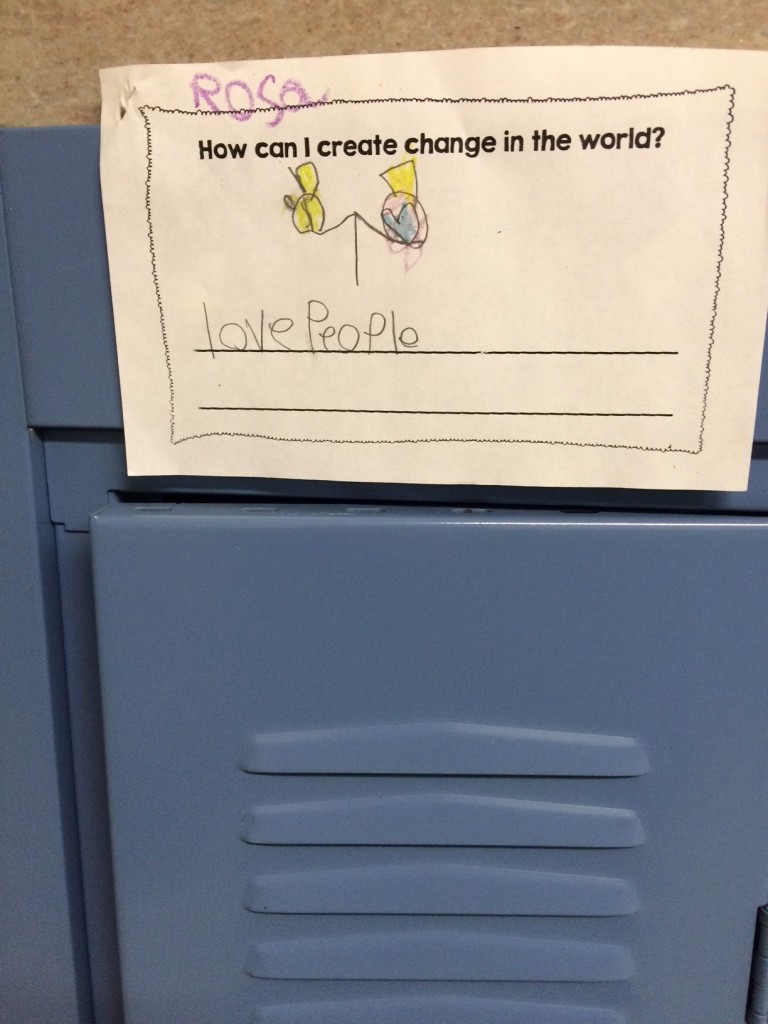

We are attempting to raise our children as followers of Jesus–thoughtful, compassionate, joyful people whose lives are defined by loving God and neighbors. We pray for God’s spirit to fill them, to make impossible things happen.