My shoulder muscles were crying as I lugged two five-gallon buckets of water, one in each hand, up the driveway. “Almost there, almost there,” I panted, trudging the width of the massive garden on my way to the front door. Three steps up, and… there! Stepping into the hostel, I sighed long and grinned, wordlessly confessing my exertion to everyone gathered in the kitchen. The other guests returned my smile—none of us were really used to this. We were off-the-grid tourists, short-term visitors from a planet with running water, hobby gardens, and cellphone coverage.

We were not sure we could keep this up for very long.

But we were glad—so very glad—that our hosts did. And we were grateful to be welcomed into this place. this place where you watched your dinner grow and pulled your water from the ground.

It was good to be on Deer Isle.

* * * * *

It seems ironic that I discovered the Deer Isle hostel on the internet. My husband and I had longed to visit Maine for most of our ten-year marriage, and our anniversary was the perfect excuse to make the trip. I started at the state tourist website, clicking the ‘hostel’ tab mostly out of curiosity. We were cheap, yes, but we also wanted our own room.

Deer Isle Hostel was a top choice, and as I clicked through, my curiosity grew. It was owned and run by a married couple, Anneli and Dennis, who were named ‘Homesteaders of the Year’ in 2013. It was off-the-grid, hand built, and 17th-century inspired. It was solar powered, with hand-pumped water and a hot outdoor shower.

I wasn’t sure I knew what all these things meant. I kept reading.

Every night there were communal dinners from the garden. It was a short hike from the ocean. There was an inexpensive, secluded hut for two. Now we were talking.

I sent an e-mail, a reservation, and then a payment, still having very little idea what we were getting ourselves into.

* * * * *

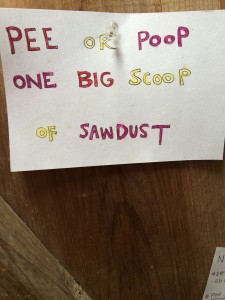

When we arrived at the hostel in early August we were greeted by Dennis, who turned out to be a wiry man-of-Maine with a smile covering half his face. He greeted us enthusiastically, showed us our hut, and then introduced us to the bathroom facilities. The toilet, which was actually a five gallon bucket in a toilet-like frame, was accompanied by a big sack of sawdust. We read the cheerful sign:

We also noticed that the bathroom smelled pleasant, not at all like the outhouse we were expecting, but like peppermint hand soap and clean sawdust. It smelled better than our bathroom at home–so much for roughing it.

The shower was next. It was, indeed, outdoors, with high wooden walls and a view of the sky. Dennis pointed to a huge (and again, not smelly) compost pile next to the shower, and showed us the end of the black tube winding its way through the pile. “This is what heats the water,” he announced joyously, almost as if he had come up with the idea yesterday and is still shocked that it works, “and the hot water tube comes out here, next to the cold.” Now he unhooked a silver watering can from above our heads. “Just mix your hot and cold in this. Then hang it back on the hook, and tip it forward when you want water. It’s that simple,” he declared, and he was right.

These people, I thought, have got this down.

* * * * *

We stayed for nearly a week, and I was surprised by how easy it was to settle into the rhythms of daily life. The things that I thought would be challenging, or at least notable–the toilets, shower and all other things water-related–turned out to be surprisingly unremarkable. There were systems in place long before I got there; the patterns of life were well-established.

There was something so good, so refreshing, about stepping into rhythms of life that made sense.

Every night before our communal dinner, everyone gathered near the long table. We grabbed each other’s hands, paused for a moment of silence, and then went around the circle, introducing ourselves and stating something we were grateful for in that day.

Because we were there for a week, I started to notice a pattern in Anneli’s responses. Everyday she was grateful for her guests, her husband, Dennis, and her swim in the pond. The first two I expected, but the third seemed more peripheral, even trivial, especially when she said it for the fifth day in a row. Then, one day, she explained.

Anneli grew up in Northern Sweden and thus knows what it means to savor the summer. She brings this appreciation to her life in Maine. “There are one hundred days of summer,” she said, “and I have committed to swim on each of these, each and every one of them. Summer will soon be over, and so I am grateful for every swim.”

Later, as I reflected on her response, something new occurred to me. I had been admiring Dennis and Anneli for creating this place called Deer Isle Hostel and for organizing their lives (and mine, for a week) around sustainable practices. But, while these things are true, more is going on here. They are not only creating place; they are receiving place.

In choosing to live so closely to the rhythms of the very specific place they inhabit, they are not only vulnerable to its quirks–destructive storms, long winter months, hungry groundhogs, invasive pests–but they are also open and receptive to its very specific gifts–one hundred days of warm air and cool pond water, a garden big enough to feed hostel guests in the summer and still eat throughout the winter, and a compost-hot shower covered by sky.

And though I don’t see a sawdust toilet anywhere in our future, I do carry this question with me:

Now that I’m home from Deer Isle, how can I receive the place where I live?