The world looked calm and vivid and possible.

~ A. Alvarez

The New Year brought sun. I awake to a teeny rainbow projected on our bedroom wall, courtesy of the light reflected off a prism-shaped rod hanging from our blinds. Even with the blinds closed, the light peeks through, catching a corner of crystal and bending, working its magic on the morning. It is joy.

I go through the rest of the house opening blinds, and a memory comes to me of Mom and her morning routine. Mom in her robe and slippers, hair still up in bobby pins, lighting lamps, opening drapes, winding old clocks with old keys. She’s done this every day for umpteen years, and today I see her again heading for the fireplace, finding the key, removing the glass dome, winding the back of the clock. Two or three turns, maybe it was more. I begin to wonder: What became of that old clock?

That bright, January morning I find myself wondering about other things, as well. About what it was like to be in the home she loved, in the neighborhood that was just right, in the middle of the family that depended on her. What was it like to leave all that and start over at age seventy?

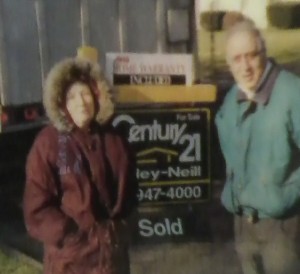

Mom did not say. I’m sure she felt she didn’t have to. She probably sold the old clock, along with the baby grand and organ and other things she loved, including the house, in order to make way for the next stage of her life. The car would go next, and, with it, a lot of her independence. I’m not sure she was sad to see them go, but I’m not sure she wasn’t. Mom did not say.

If Mom was making a statement by selling away her former life, item by item, it was totally lost on me. In 1996 I was only forty-two, so I was young. I still had a few kids at home, and one about to be married. Yes I remember 1996, not because of what was happening to me but more because of what was happening around me. But time has moved us along and now I have a “child” the same age as I was back when Mom sold the family home along with most of its contents and moved into a retirement village. Mom made a decision to change her life. It was her decision to make, even if none of us kids agreed or understood.

Oh, we made our opinions known. We argued with the folks. Mom was not interested in our opinions, nor was Dad, who seemed content to simply do it Mom’s way for once.

Now time has moved us all on. Twenty years have come and gone and I’m the mom making life-changing moves that are probably quite curious to my children. My grown children who argue with me. And make their opinions known.

And do I listen to them? Yes. And no. Because of Mom I’ve been educated into the world of moving on. Mom was strong enough to do what she felt she needed to, even if we saw it as giving up something she loved. I’m the same girl she raised and then let go, I’m the daughter always reaching for more life, not less.

Perhaps I still don’t understand why Mom wanted to let go of the old house, but then I don’t really need to know. I knew Mom. I know myself. And that’s all that’s needed.

* * * * *

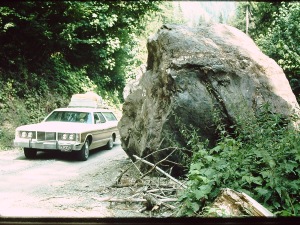

“Winding Clocks” is by Doreen Frick, a 61-year-old Baby Boomer who was born in Philadelphia. She moved away in 1976 (at age 22) to live in a bus in Washington State (see her book, Hodgepodge Logic). In doing so, she looked at life through a whole new set of values and with a whole new appreciation for the place of her youth. This year, she again pulled up roots and moved, this time to the Heartland. Doreen lives in Ord, Nebraska and has been published at Boomer Cafe.

“Winding Clocks” is by Doreen Frick, a 61-year-old Baby Boomer who was born in Philadelphia. She moved away in 1976 (at age 22) to live in a bus in Washington State (see her book, Hodgepodge Logic). In doing so, she looked at life through a whole new set of values and with a whole new appreciation for the place of her youth. This year, she again pulled up roots and moved, this time to the Heartland. Doreen lives in Ord, Nebraska and has been published at Boomer Cafe.