The first job I ever had was in a library. I was seventeen, bored, and in need of cash so I put away books for a whole year. The library was small with one large main room with computers in the center, a children’s nook and video shelves to one side, and fiction stacks and study carrels to the other side. There was a dark little room off to one side with biographies and Sci-Fi and probably every single book L. Ron Hubbard had ever published—no small amount of wall space for that collection.

I spent a lot of time shelving in that little back room—Howard Stern’s Private Parts, Fran Drescher’s Enter Whining, Piers Anthony’s omnibuses, and at least three times a day, multiple copies of Hubbard’s Battlefield Earth. It was the nineties and people were gobbling up books written by stars and adapted for the big screen or television by the same stars. It’s funny to think that these books have likely been carted out many times over the past ten years with fifty cent stickers on them at library book sales.

In that back room, I was accosted by a man wearing what could only be described as a strap-on. It was plumed and colorful—almost a holiday outfit, if you could outfit that particular zone. He told me he was taking a survey of people’s reactions. At first I didn’t know what he was referring to. He was obliged to gesture at his varicolored nether regions. I laughed because I thought it was funny and shelved two Battlefield Earth’s. He disappeared. I told a librarian about the encounter, and she let me know that that was not OK. It was not OK at all. An interview with the police after my shift rounded out my education on how not OK it was to be flashed.

In graduate school I worked in a research archive. I catalogued children’s books in an enormous cement basement with motor-powered movable stacks. I was often the only person there for hours at a time. Patrons stayed safely behind glass doors upstairs in full view of the archivists. There was no way anyone who did not have business there could cause a commotion. The librarians and archivists stayed in their offices, oblivious to the public; what mattered was the materials, not people. Patrons came in to look at Charles Olson’s personal papers, or eighteenth century chapbooks. There had to be a specific reason to hang out there. I determined that I would never work in any other kind of library.

* * * * *

Seven years later I found myself without a steady job, living in a new location, but with seven or eight applications submitted to libraries in the area. “This time it’ll be different,” I said to myself. “I love libraries. Always have.”

Of course I love them. I have only worked in libraries for a total of three years, but I have spent time in libraries my whole life. After months of applying, I received an invitation to work as a substitute library associate on the weekends. I found myself wheeling around the wooden cart, shelving books, and being schooled in how to alphabetize properly by a well-meaning associate. I was right back in high school. There were no flashers—that might only happen once in a lifetime—but there were many confounding problems of the twenty-first century to negotiate.

One patron asked me to help him write a letter to Donald Trump: “Dear President Trump” it ran, “I suggest you consider Russia as a top tier ally when you take America.” Another patron explained to me that he was allowed to visit the Ukrainian brides website on the library computers. It wasn’t porn. He’d already gotten the OK, alright?

I stayed for three months. It was all I had in me.

* * * * *

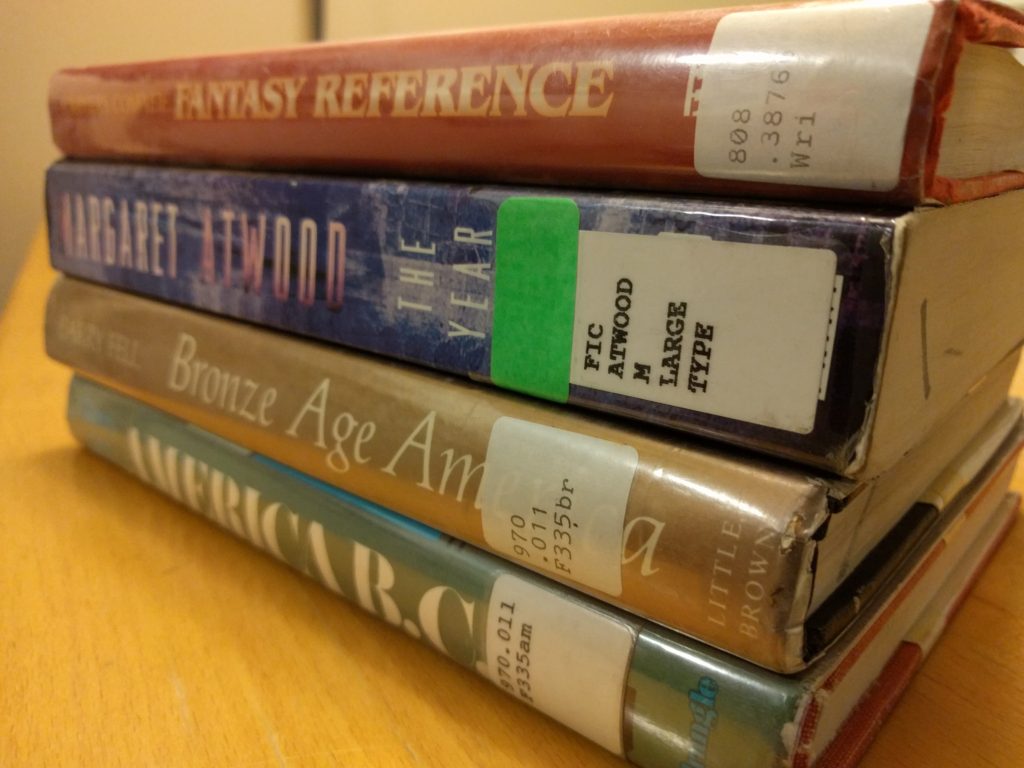

There’s nothing more exciting to me than backpacking in the library, carrying around tiny papers with call numbers written on them, finding the corresponding books in the stacks. Just today I picked up Barry Fell’s Bronze Age America and America B.C. on a whim. Alternative, badly received pre-Columbian history might help me write my book. Who knows? Libraries are pools of glorious random finds.

There’s nothing more exciting to me than backpacking in the library, carrying around tiny papers with call numbers written on them, finding the corresponding books in the stacks. Just today I picked up Barry Fell’s Bronze Age America and America B.C. on a whim. Alternative, badly received pre-Columbian history might help me write my book. Who knows? Libraries are pools of glorious random finds.

But there’s one thing I now know. Visiting a library and working in one are two different things. They might as well be two completely different places.

* * * * *