In my forty-seven years, I’ve been all over the world, but all it takes are a few cues to haul me back to my childhood.

A certain sharp and damp and lumber-ish smell brings me to my grandparents’ farmhouse in Michigan (a smell it retains years after their deaths and despite my cousin’s attempts to eradicate it). Outcrops of red, grey, and black veins of Great Canadian Shield rock bring me back to camping trips and weeks at the cottage.

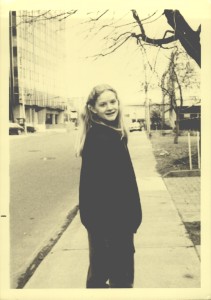

But the capital-P Place where I feel the instant settling of my spirit that says “home” is the big city sidewalk.

Settling the spirit might be an odd response to a place that’s loud and busy and can be crowded and chaotic, but that’s where I grew up: in the middle of the great city of Toronto, Canada. Truly in the middle: one block from the main north-south thoroughfare of Yonge Street, and two-thirds of the way up our subway line.

I was taking the subway by myself to school, walking ten minutes to church and seven minutes to the library, and biking three minutes to my choice of neighborhood parks by the age of nine. Despite my directional impairment (not a real disability, just a foible), I could get everywhere, because most streets were arrayed in an easy-to-understand grid. City sidewalks meant freedom.

They also meant relative safety, because there were always other people walking around, going about their business. I say relative because I was ten the first time an adult man cornered me in public and asked whether I wanted to have sex, and I can’t even count the number of catcalls I received. But these were annoyances, not threats. As long as the sidewalks were busy, I felt safe from serious harm. And they were almost always busy in our neighborhood, night and day.

In Grand Rapids, Michigan, the small American Midwestern city where I attended college in the late 1980s, there were no busy sidewalks. The busses stopped running at 5 p.m. The city center was an undeveloped ghost town. With no driver’s license and no car, I walked and took the bus or my bike – but only during the day. No people around at night meant no witnesses to possible danger, so I never went out alone after dark.

Every time I went back to Toronto during college, the first night, I’d head to the sidewalks for a walk by myself. Heat from the sun no longer rose off the cement, so the air was usually crisper. People didn’t rush the way they did during the day; they laughed and lingered on the sidewalk, which made a simple stroll feel like a celebration. It was my favorite coming-home ritual, better even than my first bite of a Coffee Crisp candy bar.

When I left Grand Rapids for New York City, I vowed never to return. “Never” lasted five years. Today I’m back in Western Michigan, and while many great, big-city things are happening here now (a better bus system, tons of businesses downtown, and multiple arts festivals that draw crowds during certain times of year), busy sidewalks in my neighborhood is not one of them. Which made it tough when my daughter reached the age I’d been when I started to roam freely.

I wanted to set her free, but my experience on those city sidewalks I love so much taught me that men in the street can’t always be trusted.

If safety is in numbers, and there is no quorum of the public generally around, no shop owners always at their stores with well-lit windows, no nosy older folks sitting on their stoops or leaning out their windows to keep an eye on things– how could I let her go?

But I had to let her go forth on our empty sidewalks. Alone. I so valued my independence as a child, that I couldn’t keep her from experiencing the same sense of competence.

My solution, since I first let her travel alone to her friend’s house across the park at the age of nine, has been to make her take her bike, since she could get away from uncomfortable situations faster than she could on foot. But still. Can I confess that I’m relieved that her best friend now lives four houses up, so I’m 95% comfortable letting her walk over? But only 95%.

Now that she’s fourteen, I set her free as often as I can, and encourage her to head out with her squad. What will cue her memories of freedom when she grows up? It won’t be the big city sidewalks that I still daydream about, but I’m determined that it will be something.

* * * * *

“Big City Sidewalk” is written by Natalie Hart. As the child of an entrepreneur, she only wanted a “normal” job when she grew up. Yet she’s wound up as a writer who is going all-in to indie publishing, simultaneously preparing a book of biblical fiction for publication this summer, and a Kickstarter campaign for a picture book for children adopted as older kids. Although she grew up in Toronto and Brisbane, and has lived in the mountains of Oregon and three of five boroughs in New York City, family and cheap real estate drove her to West Michigan. She blogs at nataliehart.com

“Big City Sidewalk” is written by Natalie Hart. As the child of an entrepreneur, she only wanted a “normal” job when she grew up. Yet she’s wound up as a writer who is going all-in to indie publishing, simultaneously preparing a book of biblical fiction for publication this summer, and a Kickstarter campaign for a picture book for children adopted as older kids. Although she grew up in Toronto and Brisbane, and has lived in the mountains of Oregon and three of five boroughs in New York City, family and cheap real estate drove her to West Michigan. She blogs at nataliehart.com

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.