Even before we were married, Ben and I enjoyed dreaming together about where we might live someday. Sometimes we explored the possibilities of different geographical locations, but more often we discussed the details of our future house. While we plotted ideal but realistic spaces for each of Ben’s many creative interests, I struggled to know what I would do in a room of my own.

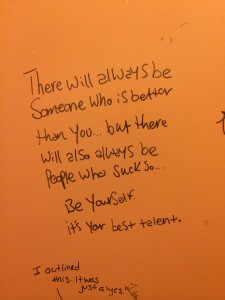

I was a very imaginative child, but even from a young age I set impossible standards for the things I created. As I grew older, I took classes to teach me the “correct” way to create. I enjoyed art, writing, and music, but there was always someone better than me. I grew weary of feeling like a mediocre imitation of someone else.

After college, life was filled with expectations to meet—job interviews, performance reviews, housework, bills. I wanted something that was mine, with no one telling me what to do or how to do it. I didn’t fully realize it at the time, but as I struggled to find where I fit in the adult world, I needed a place where I felt free to experiment, make mistakes, and try again.

Simply the act of verbally setting aside space for me to create, even before Ben and I had the means to make it a physical reality, was powerful. The point wasn’t to be fair, making sure each of us occupied an equal allotment of square footage. Instead, it was about recognizing me as a creative being. We were investing in who I was and what I could create, without guaranteed results. My room was a gift of possibility, not something I had to earn. I was entrusted with resources before proving I would use them wisely and well.

Knowing I had space with no strings attached gave me permission to take my time and explore. I didn’t have to try to measure up to anyone else’s standards. I could rediscover my creativity my own way. Setting aside physical space to create gave me the internal space to start believing in my creativity again.

In our 525 square foot newlywed apartment, we carved out slivers of creative space. Our bedroom was small, but it became more than a place for our bed and our clothes. Amidst Ben’s drawing easel, computers, and musical instruments, I found room for a sewing machine I purchased from a thrift store. Choosing a less common pastime relieved some of the pressure to perform, and, as a tall woman generally unimpressed with fashion trends, the possibility of making my own clothes appealed to me.

In our 525 square foot newlywed apartment, we carved out slivers of creative space. Our bedroom was small, but it became more than a place for our bed and our clothes. Amidst Ben’s drawing easel, computers, and musical instruments, I found room for a sewing machine I purchased from a thrift store. Choosing a less common pastime relieved some of the pressure to perform, and, as a tall woman generally unimpressed with fashion trends, the possibility of making my own clothes appealed to me.

A heather gray pencil skirt was one of the first projects I tackled. I even sewed a back vent instead of just a slit, not realizing it was a more advanced option. I just preferred the way it looked. I didn’t have any sewing patterns and didn’t know how to use them anyway—I made things up as I went, cutting into a 25-cent piece of clearance fabric after examining a skirt I already owned. The resulting skirt isn’t fit to be worn in public—the seams are unfinished, the hem is crooked, and the zipper insertion is appalling—but it still makes me immensely proud.

When the time came to move from our first apartment into our first house, we only looked at homes with at least three bedrooms. Of course we needed somewhere to sleep, but we also wanted to finally each have a room of our own. The house we purchased was old and the bedrooms were small, but they were ours to arrange and use however we wanted—places to experiment freely without worrying about the mess. After the crowded drabness of our apartment, our house was full of character. Built in 1926 in a logging town, it had beautiful birdseye maple floors and decorative molding above the doors and windows. I painted the walls of my room a soothing mid-tone blue and furnished it with dumpster dives, free finds from Craigslist, and anything that made me smile.

It was hard to leave my room behind when we moved to a new city, but I still have a room of my own. For now we’re renting and I’m not allowed to paint the dingy white walls. Bits of thread and fabric beneath my sewing table tangle in the utilitarian brown carpet. But when I feed the coral colored satin and lace of the bridesmaids dresses I’m making for my sister’s wedding under the presser foot of my thrift store sewing machine, I feel completely at home.

* * * * *

“A Room of My Own” is by Johanna Schram. Johanna feels most comfortable in places that are cozy and most alive in places that are spacious. Though the city changes, Wisconsin has always been the state she calls home. Johanna is learning to value wrestling with the questions over having all the answers. She craves community and believes in the connecting power of story. Johanna writes at her blog joRuth to help others know themselves and find freedom from the “shoulds” keeping them from a joyful, fulfilling life. She can be found on Twitter @joRuthS.

“A Room of My Own” is by Johanna Schram. Johanna feels most comfortable in places that are cozy and most alive in places that are spacious. Though the city changes, Wisconsin has always been the state she calls home. Johanna is learning to value wrestling with the questions over having all the answers. She craves community and believes in the connecting power of story. Johanna writes at her blog joRuth to help others know themselves and find freedom from the “shoulds” keeping them from a joyful, fulfilling life. She can be found on Twitter @joRuthS.

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.

The iO building was located at 3541 North Clark, kitty-corner from Wrigley Field. It was not the ideal place for a theater. To get there, I nudged my way through Chicago Cubs foot traffic and mobs of bros who reminded me of my ex-boyfriend. I’d snake between cooing street vendors offering tickets from their back pockets and water bottles from blue coolers.