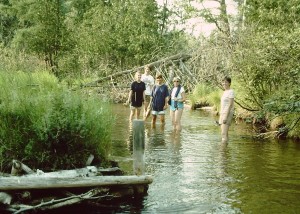

It existed once, if only in our collective imaginations. It was a secret place, a sanctuary of my childhood.

There the tall evergreens intertwined with the clouds, forming an impossibly high ceiling and muffling the noise of life beyond its borders. The ground was soft with long pine needles, perfect for the bedding of small animals, runaway orphans, or clever kings and queens. Monsters, dragons, and bad guys were often a threat, but we were very, very brave. And of course, there were also long periods of peace when there was nothing to do but rearrange the castle, look for treasure, or set up cages for the pets.

‘Can I be the queen today?’ ‘The stable is over here.’ ‘Oh no, the lady who’s looking for us is behind that bush—hide!’

There, tucked under the pines, we could see it all. We could see the magic that was always, in those days, coloring the edges of what grownups insisted was real.

* * * * *

Real. The sound of my mom trying not to cry on the phone was real. “I have some very sad news,” she said, and I leaned on the concrete wall that divided my property from the neighbor’s. “Dad,” I thought, “it’s dad.” A week before my dad had a heart attack; he was still in the hospital. “Dad,” I thought, and wondered, in the split second before my mom spoke again, if I could bear to hear the news.

“It’s not your dad,” she said.

I exhaled, and she continued. “You remember your friends up on the hill, from when you were little? Emily, and her brother? She died. It was in the paper. She took her own life. She had some problems with drugs.”

I leaned hard on the wall. I hadn’t thought about Emily for years, hadn’t seen her for decades. All I could remember, through the cloudy vision of childhood, was our shared world under the tall pines.

* * * * *

As I scrolled through the remembrances on the funeral home website, I knew this–I do not mourn as those who knew Emily mourn. I wouldn’t have recognized her on the street. I learned about her adult life by reading her obituary. She was a writer and an editor. She lived in Boston. She had a Siamese cat.

A real Siamese cat won’t stay in a cage made of pine needles.

And a magical childhood can’t save you from the deepest kinds of grown-up despair.

* * * * *

In my own grown-up world, it been a hard and beautiful summer, heavy with sickness and sadness, light with outdoor adventure and the laughter of our daughters, now eight and almost-seven.

The youngest took me for a walk in the woods behind our house tonight, an urban forest full of sprawling vines and broken glass. “Do you want me to show you around?” she asked. “Of course,” I said hesitantly, “But maybe we shouldn’t be wearing flip flops.”

“Mama, we’re fine. Just be careful. Did you know that all the trees have names?” She led me down a path, speaking to several maple seedlings, “Hi Jack. Hi Bella.” I asked her how she knew the names, and she traced the bark with her small fingers. “The markings tell me, Mama. See, this one is a girl tree named Meeka.”

I smiled at her, but suddenly, I felt afraid. Emily and I had created our own imaginary world, but it hadn’t endured. What good is magic that fades? I wanted, in that moment, to lock both of my daughters in a high tower like Rapunzel, to save them from tragedy that reaches its claws into the past–into memories that seemed to belong to another world.

There is only one world.

My daughter tugged at my arm. “Mama, did you know that trees talk to each other when their leaves sway?” She moved her arms and hips side-to-side and motioned toward the leaves. “Like this, Mama. This is how trees say goodbye.”

And in this world, there is still some magic.

I looked up. The top layer of trees formed a cathedral ceiling, now a sanctuary of my adulthood. There I prayed. There I said goodbye.

* * * * *

I did not ask my friend’s family for permission to share this story, thus ‘Emily’ is not my friend’s real name.

Photograph by Noah Weiner, shared with his gracious permission.

* * * * *

Jen Pelling is a writer and editor who lives in the woods of urban Pittsburgh with two daughters, four cats, ten chickens, and a husband who keeps her sane.