When I was a little girl, I thought my daddy made all the money. That’s because when I once asked him what he did at work, he told me, “I make pennies.”

I probably was too young to comprehend the complexities of managing a blast furnace for US Steel, which is how my father actually spent his days back then. But I like to think I might have been able to wrap my five-year-old brain around it to some extent. Instead, I spent quite some time believing that my father worked in a penny factory.

To be sure, he was compensated for his actual work with many, many pennies—and nickels, dimes, quarters, and dollars. Because of this, my life growing up was very different from his.

***

I remember my dad once telling me that, when he was a teenager, his greatest fear was that he would never make enough money to feed himself. For years, he never felt full. He was always hungry.

As the ninth of twelve children born to a Ukrainian immigrant coal miner, my father wore the hand-me-down clothes of his older brothers. He used to joke that his shoe size matched his age until he was 14. Unfortunately, he often had to wear shoes that were a size or two smaller than his feet; the bumps on his toes bore witness to that for the rest of his life.

In 1913, the 18-year-old boy who would one day be my grandfather left his home in a rural village in western Ukraine to cross an ocean to join his older brother in a strange land. After he arrived on Ellis Island, in full view of the Statue of Liberty, he had to wait for a stranger to bring him the $25 he needed to enter the country. Today, that would be approximately $610.

My father was born nearly 30 years after his father’s passage to the United States. In 1959, my dad graduated at the top of his high school class. He was awarded a football scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, where he ultimately earned a degree in mathematical engineering.

After four years of college, my father was drafted by an NFL football team. After a single season as a rookie with the Kansas City Chiefs, he decided to finish his five-year engineering program at Pitt. He spent the next few decades working his way up the corporate ladder of the American steel industry, even when that industry was in danger of collapsing.

“I sure am glad my dad caught that boat.”

I can’t even begin to count the number of times I heard my father repeat those words.

***

“Our money isn’t really ours in the first place,” I explained. “It belongs to God. Everything belongs to God. We’re just meant to take care of it and to use it well.”

“Our money isn’t really ours in the first place,” I explained. “It belongs to God. Everything belongs to God. We’re just meant to take care of it and to use it well.”

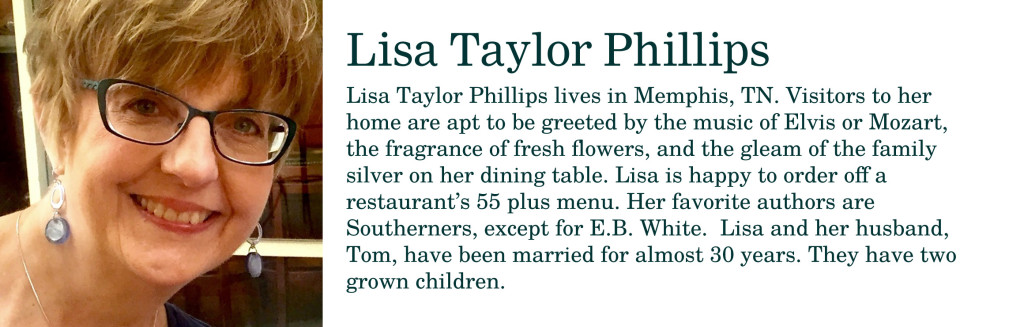

I was sitting in the passenger seat of my boyfriend’s car, explaining to him the finer points of—and theological reasons for—support-raising. He was a first-year medical resident, trying to wrap his brain around why his girlfriend had chosen to work for a campus ministry organization where she was expected to raise a portion of her salary.

My father, who generously and fully financed all four years of my college education at a prestigious liberal arts college, was similarly puzzled by my decision. The philosophical and theological underpinnings of raising support were a mystery to him. He didn’t understand my counter-cultural choice of career, but he supported it.

My father continued to financially support me and my work until his death in 2013. Dad offered his support because he loved me. He supported my desire to use my gifts to do work that fulfills me and that makes a positive difference in the world. He never used the language of “blessing” or “stewardship,” but he embodied both with his generosity—to me, to my brothers, to everyone he met.

Because my grandpa caught that boat, and because my dad made all those pennies, I have been afforded opportunities that would never have occurred to either of them. And I am grateful.

***